With the backdrop of the ongoing pandemic, increasing global tension, environmental destruction, everyone seems to either be battling with their own mental health issues, or knows of someone who is.

But so much of the conversation currently revolves around the individual.

When people face mental health issues, it seems like it is their fault for not being able to handle the stresses of life adequately. Mental distress appears to exist in a vacuum, with the responsibility to recover also placed on the individual.

Many bite-sized social media posts suggest practising self care by downloading a mindfulness app, trying out yoga, seeking help from mental health professionals, just to name a few. While these actions are good starting points, many would argue that they are not enough.

A big piece of the puzzle that has been missing is just how big a role systemic inequalities play in contributing to an individual’s mental health issues. When we start to take into account how race, class, gender, sexuality and disability affect an individual, mental distress suddenly becomes a very reasonable response to the many stresses of life.

As trauma expert Bruce Perry and talk show host Oprah Winfrey suggest in their recently released book, perhaps everyone should shift from asking “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”, which starts to reshape the conversations on trauma and healing by considering the responses to circumstances, situations and relationships.

“In Singapore, we don’t follow the psychosocial model of viewing mental illness or distress, which takes into account the individual’s social environment and lived realities. We’re so quick to label them as medical problems whereas mental distress is just a symptom of the problem. The core issue at play is systemic oppression,” says Ms Reetaza Chatterjee, founder of the mental health youth collective Your Head Lah!.

According to Ms Chatterjee, having a political analysis of mental health is important as it is an issue that disproportionately affects marginalised groups. As a brown and queer individual, she came to that realisation when she entered the psychiatric system herself, and underwent the process of therapy and medication, to no avail.

“I thought the solution was to try to fix myself. But even after going through all the treatment, I realised that I was still not well, because I was still facing the violence of racism, homophobia and capitalism everyday. I realised that what we need is collective fixing because it’s difficult to heal when the wounding is constant,” she says.

“The conversation needs to shift to a discussion about how mental health is linked to the systems that marginalise us. How can we resist the systems and know what resources we need if we don’t even name the systems that oppress us?” she asks.

What happens when the wounding is constant?

Trauma-informed practitioner Lee Yoke Wen stresses that trauma can happen on a larger scale, to entire groups of people, if processes and policies are set up in a way that disregard them, or do not ensure that they have the right to exist.

“Trauma happens when stress is overwhelming and is too much for our nervous systems to bear. For those who live in a society where they’re discriminated against, in that they’re not allowed to be who they are, or they don’t feel safe enough to express their voice, then that’s when trauma can happen to a whole population of people,” says Ms Lee.

This is also known as structural trauma, defined as the emotional and psychological damage from inequity that is enforced through public policies, institutional practices, cultural images and behaviours. They are built into the structure of the culture, and which reinforce social inequality.

In Singapore, groups that may face structural trauma include the LGBTQ+ population, migrant workers, lower-income families, racial minorities, and people with disabilities, among others.

Ms Lee used to be a social worker working in the child protection system for over 10 years, and has witnessed the limitations of a system that does not take into account structural trauma in coming up with solutions. Her job then involved working out safety plans when a family is unable to keep the child safe in their home environment.

“Every stakeholder in the system looks at the family from a different angle and considers how to stop the gap. For example, the gap may be poverty, parenting skills or lack of time because the parents are overworked, or abuse. Whatever the problem is, we find solutions that address that one problem and help the family survive for the time being,” she says.

“But my observation is that every stakeholder just looks at one piece of the puzzle. It’s like looking at an elephant—they’re touching one part of the elephant and saying, ‘Oh this is the trunk, let’s fix the trunk’, or, ‘This is the leg, let’s fix the legs’, but no one recognises the totality of the elephant, no one sees the family in its whole environment,” she adds.

Without working on policy and structural changes, these solutions just plug the gaps, she says.

“Just look at the government’s definition of what a family unit is — a heterosexual nuclear family. Think about the people that don’t get to benefit from this narrow definition of family and don’t get to enjoy government support,” she says.

Solutions that do more harm than good

Without an understanding of how structural trauma and systemic inequalities impact mental health, any solution has its limitations, and in the worst-case scenario, might even do more harm than good.

“Intersectionality should be a bigger part of the mental health conversation because we have to take a holistic approach when looking at an individual’s mental health. Especially if you’re a mental health professional, it’s important to understand all the factors contributing to a patient’s condition,” says Mr Didi Amzar, a volunteer at Resilience Collective, a peer-driven mental health collective.

The peer volunteer cited an example of a friend who went to therapy and was narrating how experiencing micro-aggressions had affected her self confidence, but instead was met with dismissal and shut down. Her therapist had said that these incidents were not important and did not contribute to her trauma. Following that incident, she stopped talking about race altogether with the same therapist and only realised months later that she should have just switched therapists.

“It’s extremely hard and expensive to find therapists who understand how institutional racism works or are queer affirming — which is especially what a marginalised person dealing with a lot of trauma needs. The process of meeting horrible therapists can be quite traumatic in itself,” says Ms Chatterjee.

Keep questioning the status quo

The current conversation on mental health still exists within the parameters of the status quo, but to move the conversation forward, we need to start questioning the current systems, keep challenging the status quo.

“When we start to name the systems that oppress us, only then can we begin to dismantle them and figure out what resources we actually need,” says Ms Chatterjee.

Agreeing, Ms Lee says that it’s important to recognise our own privileges. “It may be an uncomfortable exercise because so many of us are benefitting from these barriers that other people are facing, benefitting from the current system—but it’s necessary,” she says.

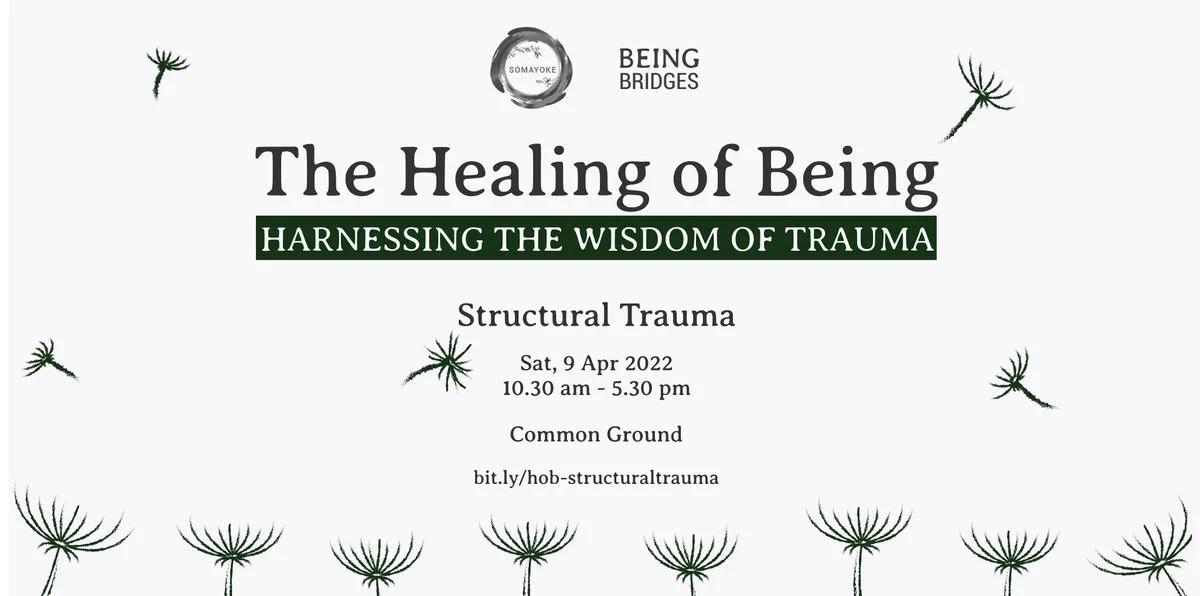

To raise awareness about structural trauma in Singapore, Ms Lee is hosting a series of talks that uses the film Wisdom of Trauma by physician and trauma expert Gabor Maté as a starting point.

“When we conducted our first session, people initially came in very curious. But when they realised they may be part of the problem, people started getting very uncomfortable. That’s part of the process. It’s important to notice the discomfort, and acknowledge where it’s coming from, what it’s trying to tell you. Is it coming from the larger environment that we are living in? Because these systemic factors do inform our personal traumas. The personal is always linked to the collective,” Ms Lee says.

In addition, a conversation about our shared humanity and sameness is important, she says. “If you look a marginalisation, oppression, discrimination—all of these highlight the differences between ‘us’ and ‘them. But at the end of the day, we’re all humans, and we get hurt by the same things. We also find strength when we are given the same support, when we are given the space to feel seen and heard.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.