Community group Transformative Justice Collective has received some 20 letters, from Singapore and overseas residents, written to Syed Suhail, a Singaporean man on death row. The collection was part of a letter-writing campaign that the group launched in March with hope that the letters would provide a source of comfort to Syed. As part of the collective, freelance journalist and anti-death penalty activist Kirsten Han tells us more about the campaign and why she is against the death penalty.

Singapore’s death row can sometimes feel like a black hole – people get sent there, and, as far as the Singaporean public is concerned, vanish.

A public opinion survey conducted in 2016 found that 62 per cent of 1,500 respondents reported knowing little to nothing about the death penalty. About half said that they were not very interested or concerned about the issue. But even people who are interested in the matter are hard-pressed to find solid information about death row, and details of the application of capital punishment in our country.

Anti-death penalty activists like myself aren’t allowed to visit and interview the inmates in prison, so most of what we know about death row has been pieced together from snippets of information passed on by their family members. Some turn out to be false, the result of incomplete memories or miscommunication. Others might be true, but prove impossible to verify – like when an inmate tells his sister that someone had been executed last week but he only knows their nickname, which can’t be matched to official court judgments or news reports.

This is what we know: Death row inmates spend most of their time alone within the concrete confines of their cells, and only have one hour of “yard time” – which means they can go to a sort of recreation room – a day. They are usually allowed one visit a week from immediate family members, lasting about 40 minutes. But if they’re being executed at dawn on the Friday of that week, they get to have visits in the mornings and afternoons from Monday to Thursday.

Being in prison is like being displaced; the pace of regular life replaced with the regimented rhythms of incarceration. Any contact with the outside world, from trips to hospital for medical check-ups to letters to family visits, is regulated and mediated by the prison authorities. Recently, we’ve even found out that private correspondence between death row inmates, their families, and even lawyers, had been copied by the prison and forwarded, without consent, to the Attorney-General’s Chambers. While these are conditions that might cut across the entire prison population, death row inmates endure this while also waiting for impending execution. It’s an alienating, dehumanising experience, difficult for any of us outside to truly understand or relate to.

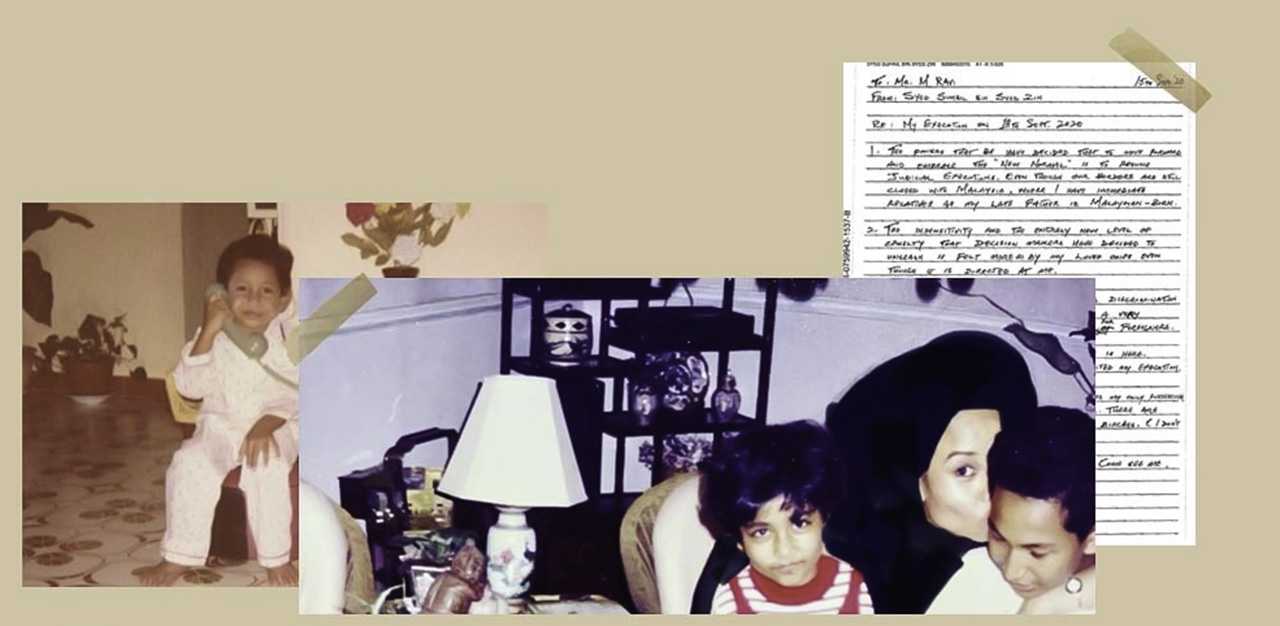

Late last year, some friends and I got together to form the Transformative Justice Collective to research, document, and advocate for reform of Singapore’s criminal punishment system, with abolition of the death penalty as one of our priorities. Although we’d already been vocal about our opposition to the death penalty before, it was the case of Syed Suhail bin Syed Zin that motivated us to start this new collective.

Syed was sentenced to death in 2015 after being convicted of drug trafficking. He’d been charged with possession of 38.84g of heroin, which triggered clauses under the Misuse of Drugs Act that presumed he was trafficking drugs. If found guilty of trafficking 15g or more of heroin, the penalty is a mandatory death sentence, unless one can fulfil a set of narrow criteria.

Syed had two close shaves last year; the date of his hanging had been scheduled twice, and his family notified, only for the execution to be halted. What really surprised us, though, was the support for him. A petition calling on President Halimah Yacob to commute his death sentence gathered over 30,000 signatures – a much higher number than petitions for other inmates in previous years. It seemed like, after years of activists plugging away on this issue, Singaporeans are now more open to critically evaluating capital punishment, talking about how such cruel penalties do little to address problematic drug use, and considering harm reduction principles.

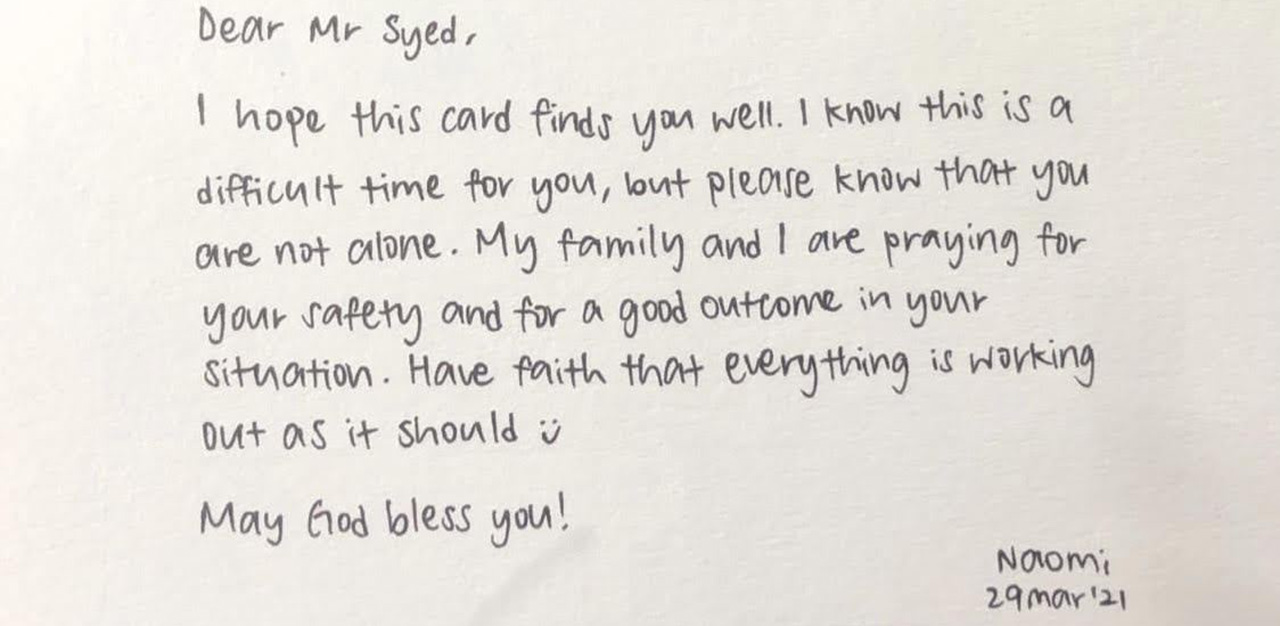

With cases still pending in the courts, Syed and his family are currently awaiting further news. To support them at a nerve-wrecking time, the Transformative Justice Collective decided to launch the #DearSyed letter-writing campaign, encouraging people to write to Syed. They can either post their letters to him directly, or e-mail/send them to us, for his sister to bring to him whenever she visits.

The idea behind the campaign is to provide Syed, generally so cut-off from the world outside of Changi Prison’s death row, with more human connections to bolster his courage and hope. At the same time, we wanted to raise more awareness of Syed’s case, and the issue of the death penalty itself. By encouraging people to take time out of their own busy routines to communicate with a death row inmate, we hope that more people will be spurred to consider where they stand when it comes to capital punishment.

The same public opinion survey mentioned earlier in this piece found that when people have more details about specific cases or the application of the death penalty, their support for capital punishment wavers. It’s easy to say that you support the death penalty when you’re thinking about it as an abstract, faraway issue, or when your considerations revolve around hypotheticals about psychopaths and evil dictators. It’s another thing completely when you learn more about how it’s disproportionately applied to drug offenders whose back stories are not as black-and-white as what the Government and mainstream media portray them to be.

People who have written letters to Syed have mentioned how testimonies from both his older and younger sisters have helped them relate more to him on a personal level. This is a rare thing for Singaporeans; while our country clings stubbornly to the death penalty, it is remarkably hush-hush about many aspects of this regime, and Singaporeans are generally cut off from any knowledge of the death penalty, or opportunities to learn and talk about the factors that might lead one to end up where Syed is now.

Although some, including myself, have already posted our letters to Syed, his sister Sharmila says that, from what he said during her last visit, he hasn’t received any of them. There’s not a lot of transparency about how the prison screens letters written to inmates, but we hope that he’ll get his letters soon (if he hasn’t already).

Nevertheless, Syed is aware of the campaign. “Syed did mention that it is incredibly humbling to hear that many people have been writing to him, and that they are showing support,” says his sister Sharmila.

When asked how the campaign made her feel, she says: “Very moved. I am always in awe whenever I see drawings/paintings… like these total strangers put in so much effort for Syed.”