THIS ARTICLE HAS BEEN UPDATED ON 28 DEC 2021

With Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats increasingly fetching seven-figure sums today, the idea of affordable public housing has blurred for many. Just a few weeks ago, a five-room flat in Bishan was sold for a record $1.36 million.

It was only 70 years ago that the term public housing had been as foreign a concept to most Singaporeans as rural slum is to many here today. Reading Calvin Low’s 10 Stories: Queenstown through the Years, one is treated to the imagery of a time forgotten; when self-built, naturally-ventilated, multi-family attap abodes lined our rural fields, and when the presence of the fabled ‘kampung spirit’ thrived alongside an absence of piped water, sewerage and electricity.

In what would have resembled the ‘black canal’ city slums we still see in some major Southeast Asian cities today, comparable conditions were observed in Singapore’s inner city slums in the 1960s by former chairman of HDB Lim Kim San.

In a 1985 oral history interview with Ms Lily Tan on the economic development of Singapore, the late Mr Lim recalled an encounter he had with a “pantless Chinatown slum dweller” whose brother had worn their only pair of pants out to work. It turned out that pair of pants was not the only thing they had to share.

“. . . they shared a bunk . . . when the one who works in the daytime is out, the one who works at night sleeps in the bunk. . . . It’s very dark and it takes time to get your eyes accustomed, adjusted,” he said.

“The smell and the [living] conditions were terrible, really terrible,” he added.

Soon after his visit to these inner city slums, Mr Lim, with the full might of the nascent Lee Kuan Yew administration, set out to “break the back” of what they deemed the most urgent social issue in young Singapore — housing shortage.

This led to the development of a public housing programme that saw the rapid building of flats, reported in a 1964 Straits Times article headlined A flat every 45 minutes. The HDB promise then was to provide a reliable roof over Singaporeans’ heads, and by 1969, a third of Singaporeans were living in 120,000 HDB flats, largely rental.

Nevertheless, a “home-owning democracy” it was not. Convinced that the sense of belonging that comes with true homeownership would bring Singapore political stability, the government leaders started to liberalise some of the public housing regulations over the years.

Among them was the easing of reselling guidelines to allow flat owners to sell to any citizen homebuyer, giving birth not only to the HDB resale market we have today, but also a public housing sector that is, in the words of Dr Phang Sock-Yong, the Celia Moh Chair Professor of Economics at the Singapore Management University (SMU), “a largely privatised sector.”

As HDB flats could now be transacted on the open market, they are subjected to similar market forces that drive property prices anywhere in the world.

Housing diverse dreams

Dr Phang pointed out in her 2015 research paper that the housing shortage problem was solved by the time Mr Goh Chok Tong succeeded Mr Lee Kuan Yew as Prime Minister.

“With 88 per cent of households owning their own homes, 87 per cent in HDB flats, the property-owning democracy had become a reality. In the 1990s, the HDB shifted its focus to providing larger and better quality flats for existing HDB and upper-middle income households, the redevelopment of older estates, and retrofitting existing flats,” she wrote.

Similarly, in his 2018 research paper on Singapore’s public housing policies, Dr Ng Kok Hoe, then Assistant Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, wrote that “an expansion of choice at the top end of the public housing market” is a response to the gradual shift in homeowners’ aspirations towards upward housing mobility.

“Economic development and higher living standards were accompanied by expectations for housing experiences that would fit with more refined lifestyles, generating a policy momentum that focused on upward housing mobility and deemphasised the provision of basic, affordable housing options,” Dr Ng wrote.

“Housing today is no longer uniformly affordable and accessible across the public housing sector.”

The myth of inevitability

But to say that Singaporeans only have their increasing affluence to blame for the substantial price tags on some HDB flats today seems like an oversimplification.

Prominent economist and vice president of the Economics Society of Singapore Manu Bhaskaran says that certain policy changes over the years have undoubtedly contributed to the flat prices homeowners today face, and that society’s rising affluence only accounts for part of it.

“Prices are high now, partly because of changes in policies such as allowing CPF savings to be used, and the change in land policy whereby HDB has to buy land from SLA (Singapore Land Authority) at market prices,” he says.

In response to Mr Bhaskaran’s comments, the HDB clarifies with TheHomeGround Asia later (on December 9) that at least in the case of resale flats, “prices are based on negotiations between willing buyers and willing sellers.”

“For public housing developments, state land is sold to HDB at the market value assessed by the Chief Valuer. The valuation is done in accordance with market conditions and established valuation,” its spokesman says, adding that it would be incorrect to conclude that the land prices for public housing are a cause of high resale prices.

While the diversification of options within the public housing programme ran on, politicians also started to peddle the narrative of asset enhancement. The Goh Chok Tong administration was of the view that HDB flats should be seen as potential sources of retirement security; that is, assets to be monetised.

In his 2015 paper, National University of Singapore (NUS) professor and sociologist Chua Beng Huat said in its effort to make public housing an adequate asset for retirement funding, the Goh Chock Tong administration pioneered an estate upgrading scheme to ensure property values of older estates were protected against subsequent new projects.

At the same time, a pricing formula for new flats valued them at a 20 per cent market discount from the prevailing prices of equivalent resale flats.

“This effectively shifted the prices of new flats from provision-base to market pricing. Hence, resale flats are permanently maintained at higher prices than new subsidised flats of equivalent size,” Dr Chua wrote.

According to Dr Chua, this, together with the estate upgrades and location advantage, meant that flat values were “practically guaranteed”.

Not long after, a serious flaw in the pricing formula surfaced. “Rising resale prices cause prices for new flats to rise; the increased price of new flats forms a floor for housing agents to increase the prices of resale flats; prices for both increase with each turn of the cycle,” Dr Chua wrote.

Price inflation had infected the public housing programme, and as Dr Chua observed, contributed to the ruling party’s devastating showing at the 2011 general elections.

The million-dollar question

Since the start of 2021, 176 HDB resale flats sold for over $1 million, topping 2020’s full-year figure and begging the question — how affordable is public housing for ordinary homebuyers today?

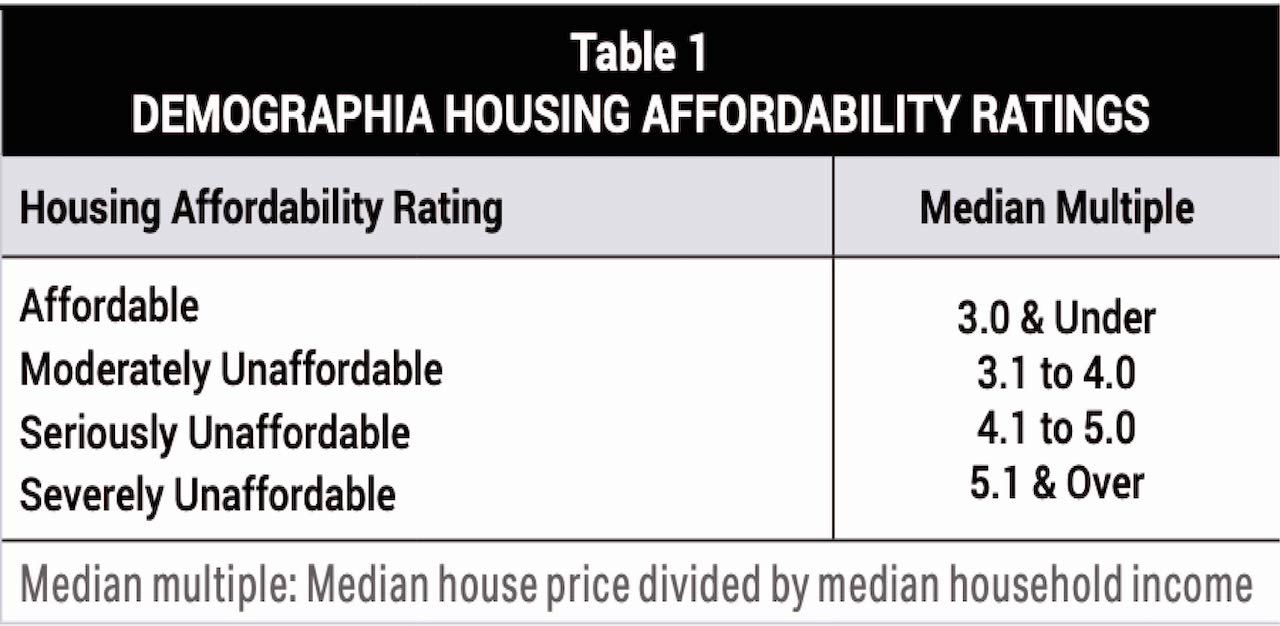

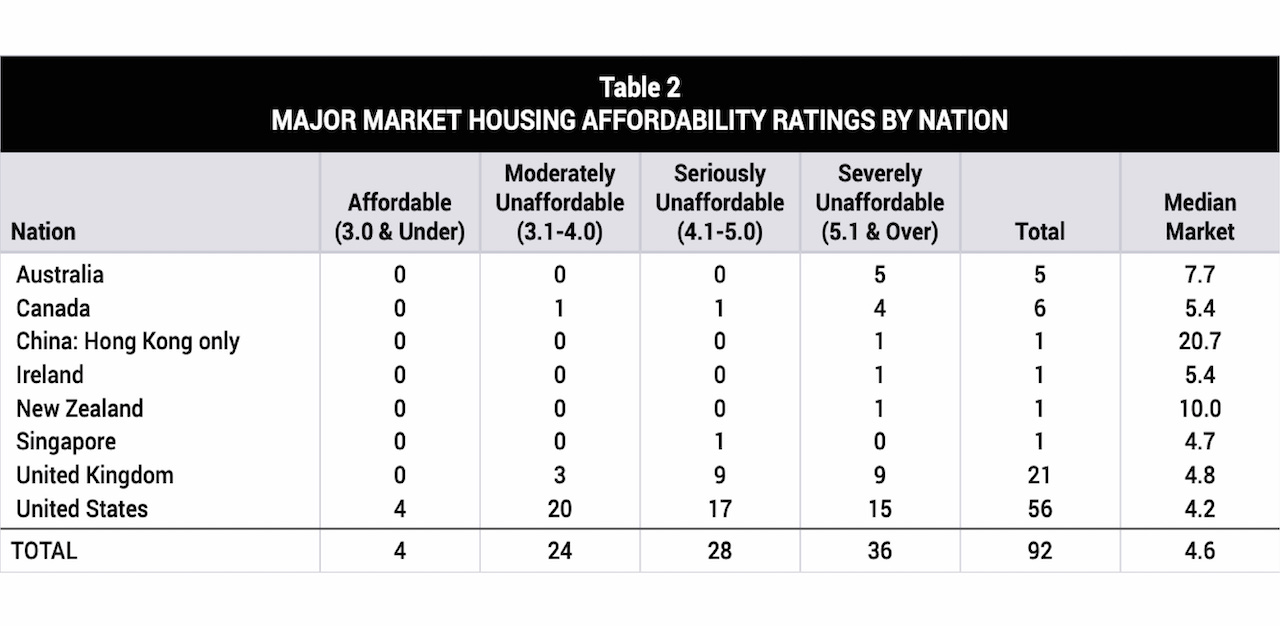

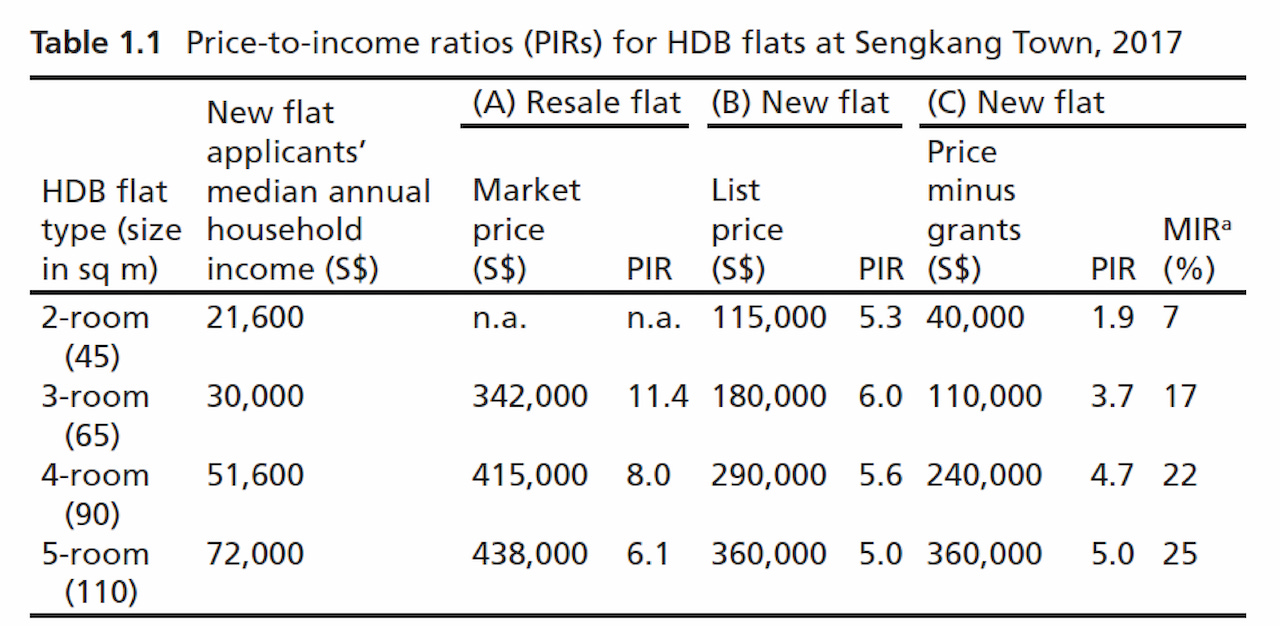

In her 2018 book Policy Innovations for Affordable Housing In Singapore: From Colony to Global City, Dr Phang cited the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey’s rating system as an accurate way to measure Singapore’s housing affordability.

She found that while resale flats are “severely unaffordable” for Singaporeans, the smaller BTO flats have been made affordable for low-income families after government grants are given. Middle-income families, on the other hand, appear to have gotten the shorter end of the stick.

Dr Phang suggested in a 2013 presentation at the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) that an “overspending on housing” largely by the middle-income may be due to “housing prices rising at a rate much faster than incomes”.

This is because in the twelve years leading up to 2012, median household incomes rose about 60 per cent, whereas the median price of a four-room resale flat almost doubled.

But what is the alternative?

In 2012, a “remedy” was floated by the island-state’s former chief planner Liu Thai Ker who, when speaking to reporters after a lecture organised by the Centre for Livable Cities, suggested returning to the “core mission” of providing affordable housing.

“We should not […] emulate condominiums — that require more expensive materials, extra this, extra that … but go back to basics, keep housing prices affordable, let residents embellish the houses, embellish the interiors,” he said.

“…we try to use whatever budget is available to create the biggest possible floor area for the people and with minimum frills, minimum decorations and so on. By minimum decorations, it doesn’t mean that the buildings are not beautiful… if the buildings are well-proportioned, they are beautiful,” Dr Liu added.

Yet with nine years on the clock and 420 million-dollar HDB flats sold, would Dr Liu’s alternate reality be palatable to homeowners today?

Ms Michelle Tan, a finance executive in her early thirties and flat owner, feels entirely comfortable with the idea of a larger space and more manageable mortgage. A Macpherson resident, Ms Tan paid close to half a million dollars for her four-room flat in 2018.

“Actually, the exterior facade doesn’t really matter to us. I’d much prefer a bigger space to play with while renovating,” Ms Tan says.

Like Ms Tan, Ms Lee Yan Ting, a 28-year-old banking executive who recently got the keys to her four-room flat in Punggol, prefers to have more space to call home. Having seen the inside of a friend’s five-room BTO flat, Ms Lee says she now understands “the difference a little more space can make”.

“I would choose the larger flat even if it were for the same price. I’d rather have more space than to care about the exterior. Plain and clean is fine. I can live with that,” she says.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.