A desire to speak up for animal rights was Jolovan Wham‘s first brush with changemaking.

“I read an article about factory farms in a magazine, and also found Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation at the now defunct Tower Books. After that I decided animal rights was what I wanted to do,” he says.

Convinced that pursuing social work would help him to achieve his goal, he majored in the subject at university, but found it difficult to reconcile his “expanding political and critical consciousness”, with his social work education, likening them to “water and oil”.

Mr Wham eventually joined the Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics (HOME), which advocates for the rights of migrant workers, as Executive Director in 2004. Since migrant worker issues were a relatively new focus in the social service sector at the time, Mr Wham shares that his team had to learn how to meet the needs of the migrant worker community through trial and error: “Everything was done from scratch.”

His experience with HOME led him to become more exposed to the challenges that migrant workers face, invoking a sense of deep outrage in him.

“I think it was impossible for me not to turn into an activist as I saw day to day, the kinds of struggles workers were facing,” he says. “Nobody seemed to care about what was happening.”

Today, the 41-year-old civil rights activist has rallied for change for various social issues, including freedom of speech and assembly.

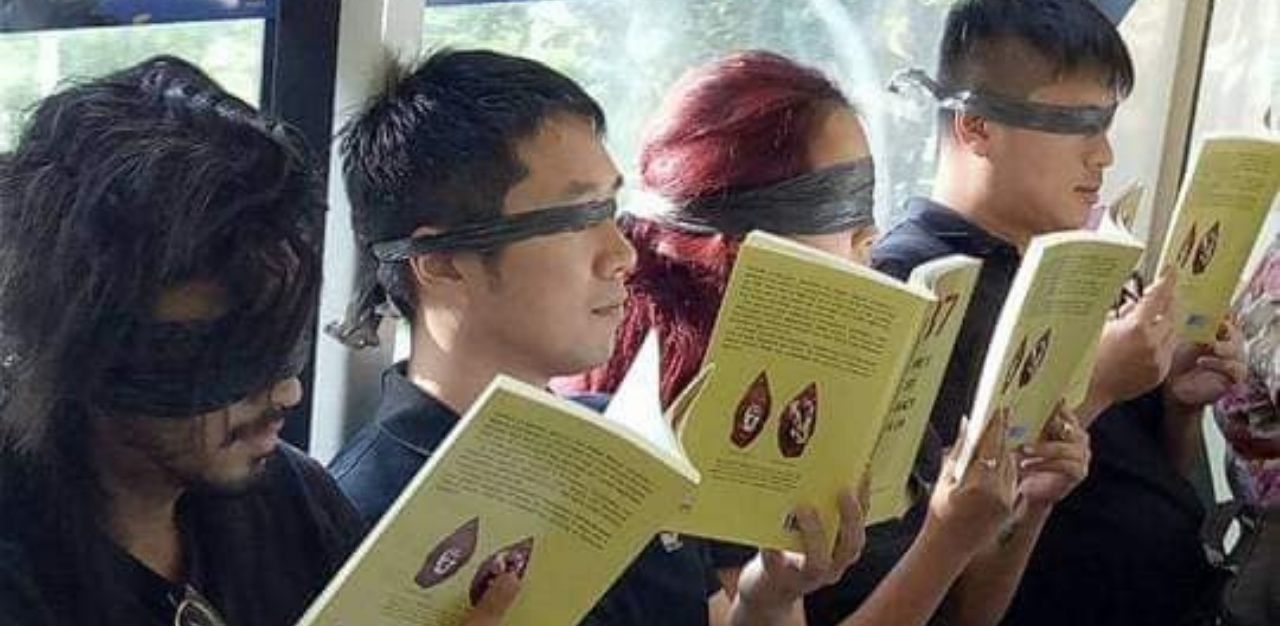

In June 2017, he held a silent protest on an MRT train, paying homage to the 30th anniversary of Operation Spectrum, a 1987 security operation that led to 22 individuals being arrested and detained without trial. Joined by six others, they wore blindfolds and held copies of a book released by some of the detainees, titled 1987: Singapore’s Marxist Conspiracies 30 Years On. His civic action led to a fine of S$8,000 (US$5,905) earlier this year, four years on, for three charges regarding the incident; he elected to serve a 22-day jail term for two of the charges.

Mr Wham is one of an increasingly vocal movement of activists and advocates in Singapore. While advocates span a variety of roles, including paid and unpaid roles in the social work sector, activists are often perceived to adopt methods such as protesting and gathering, and do so of their own volition.

But the lines between advocacy and activism can blur. For Mr Wham, they come hand in hand, with his dual roles as a social worker and activist. Defining social work as working and engaging with the communities he interacts with, he opines that it is a central part of activism. He believes that “advocacy has to be grounded in the needs and aspirations of the community you work with.”

The challenges that changemakers face

Activists like Mr Wham are just a growing number of changemakers in Singapore, with others, like Abraham Yeo, adopting a different approach to push for change.

After a series of mission trips in 2012 to help with survivor relief efforts for the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, he had an encounter with the homeless in Japan during another mission trip in 2013, where he witnessed others befriending the homeless. Inspired by his experience, Mr Yeo co-founded Homeless Hearts of Singapore in 2014. Now, the initiative is run by a group of volunteers, with the common mission of helping Singapore’s homeless reintegrate into the community.

Derek Lim, Head of Volunteering at Homeless Hearts of Singapore, shares that one challenge they face is striking a balance between protecting the identity of the homeless and advocating for their needs.

He cites the example of an individual who posted images of the homeless on social media without censoring their faces, and who even revealed the locations they were at. “Oftentimes the post is quite negative, [they don’t] really share the resiliency or the strength of homelessness,” he explains. “I think advocacy needs to be balanced, not only about the needs, but also about the strengths [of the homeless]”.

For mental health advocate Anthea Ong, entering the advocacy sector after she left the corporate world in 2013 was a change that took time to adapt to, especially when it came to her perception of effectiveness.

In the years since, Ms Ong has spearheaded numerous social initiatives, including A Good Space, Singapore’s first co-operative for changemakers. The collective aims to bring change to the workplace, foster deeper collaboration among changemakers, and create a nurturing environment that helps to sustain changemakers and their initiatives.

“My time in the corporate sector [was] always about optimising resources, maximising impact, being really creative and innovative, never really taking no for an answer,” she reveals. “But when I got a lot more plunged into this space, I felt that there was a sense [that] ‘We don’t have enough’… maybe a lot of resignation even.”

Having the awareness to ascertain the path one is taking, and the calls that one should make, are important skills to have. “You constantly have to be discerning, and make a call [about whether this is] the right path to raise awareness so that we actually see [the issue],” says Ms Ong, a former Nominated Member of Parliament.

Then there is the challenge of striking a balance between addressing issues directly, and facilitating conversations.

“How do I do it such that I’m not actually skirting around the issue, but at the same time, not compromising on dialogue or conversations?” she questions. “There is always this dance, this discussion in the centre that we are always having to contend with.”

Experience and groundedness in her purpose have helped Ms Ong to overcome this dilemma: “I tiptoe [less], I’m less concerned [about] spending all this time wanting to make sure that I sound exactly right,” she reflects.

Handling the day-to-day operations of activism, such as managing volunteers, partners, staff, managing finances, administration and fundraising, were some of the challenges that Mr Wham grappled with when he first entered activism.

Managing the notion of ‘acceptable activism’ was another, he shares: “A lot of these concerns were driven by fear. What if we lose our funding or our charity status? Will we lose support from the public?”

“How else can we mobilise resources from the community instead of feeling beholden to monetary donations from institutions, foundations and corporations?” he asks.

He thinks that it is vital to expand on present-day forms of activism.

“It’s important to explore alternatives to the current forms of activism which we have become so used to,” he asserts. “Because if we don’t, we normalise oppression, and we normalise fear. We become numb to things which we should be outraged about.”

While activism can be stressful, Mr Wham says that he has been able to manage it with the help and support of his loved ones. Humour has also been key in helping him to overcome these obstacles: “My personal philosophy is also not to take things too seriously or personally. Seeing the humour and lighter side of things is important.”

Should changemakers be compensated for their efforts?

The very communities that advocates and activists speak up for often do not have the resources to compensate them for the work they do. While those in paid positions receive remuneration for their changemaking efforts, activists and advocates who work on these initiatives in their own capacities often do not, and have to find their own sources of funding to sustain their work.

Mr Wham thinks that such activists and advocates should be recompensed for their efforts.

“We all need money to thrive and there is dignity in all labour,” he says, expressing concern about non-governmental organisations that underpay their staff members, despite having adequate resources. “We live in an imperfect capitalist world where only the very privileged can afford to do community work and activism for free.”

He also cautions against developing a martyr-like attitude towards activism: “Being passionate is important, but it should not be the overriding factor. Otherwise, we risk fetishising activism and developing a martyr mentality.”

What this does is create a “toxic inner circle”, he notes, as a way of measuring activists’ worth by their commitment and passion.

Ms Ong highlights that it is important not to idealise changemakers.

“I don’t want us to romanticise and glamorise the terms advocacy and activism, into this very charmed state of affairs,” she says.

Mr Yeo concurs: “Be humble. We are not as much of a hero as we think ourselves to be. Fellow advocates, fellow activists… we’re just doing our part to help make the world a better place in the way that we best know how.”

There is also a case to be made for advocates in the private sector, who Ms Ong says might not be top-of-mind in the public consciousness. She suggests that those in positions that involve taking care of others’ needs, such as employers and those in the human resources sector, should also play a role in advocating on behalf of the work communities they interact with.

“The private sector should be taking care of employees who are [earning] low [wages], people with disabilities… vulnerable communities, they’re all part of the working population, by and large. So employers play a role,” she insists.

Change should also be systemic, says Ms Ong.

“It’s really important that we design these advocates, ground-ups, changemakers, into our system of support,” she asserts. “It would mean… they’re part of the consultation, part of the process and part of [the] recognition and acknowledgement of the work that we’re doing.”

Aside from remuneration, she also posits that acknowledging the efforts of activists and advocates is imperative, and that there would be no conflict over the issue of recompensing them if this was the case.

“We don’t actually acknowledge and recognise people who are not paid, whether they are ground-ups, informal groups, single activists or advocates,” she opines.

Mr Yeo agrees, and gives the example of individuals who are employed by NGOs in supporting roles, as advocates. “Pay them a fair market wage without expecting them, and especially their families, to have to tighten their belts for the greater good,” he suggests. “Because justice and mercy are meant for every level of society – including paying fair wages.”

But he also thinks that those who pioneer advocacy and activism efforts should find their own personal sources of funding. And stresses the importance of integrity in establishing personal practices for fund management. One way to do this is to be transparent in one’s message to donors that funds sent directly to changemakers are for personal use, and not for the cause.

“Integrity is one of the most precious and powerful aspects of the advocate or activist’s message – and it extends to finances, especially when others give their money to you, trusting you to be accountable,” he remarks.

With that in mind, he acknowledges that advocates who do not receive compensation for what they do can also make an impactful statement.

“It makes what you’re saying even more powerful. You as an advocate are also part of the message; the medium is part of the message. [It’s telling people that] ‘It’s important enough that I’m not going to accept pay for it. Do you believe me now when I say this?’ That, I think, really does earn respect.”

Still, he emphasises the need for changemakers to be accountable for their loved ones.

“Of course if one has a family, you also have to be responsible. In the course of advocacy, you cannot sacrifice them,” he advises.

Finding sustenance as changemakers

Burnout is just one of the issues that advocates and activists face, says Ms Ong. Given the nature of the work, they often find themselves emotionally depleted, a consequence of constantly challenging the status quo.

“Emotionally it’s very draining and exhausting, and burnout is really easy to come about… On top of challenging the dominant narrative, not feeling like you’re very supported,” she says.

“We always hold out hope of some change or effect that comes from the effort that we put in. So when you put in all this effort… and then you don’t see the needle being moved… It’s really easy to get into this spiral of burnout,” she explains. “Mental well-being can very much be compromised.”

To counter this, having a strong support system is vital to ensuring well-being, says Ms Ong.

“To sustain yourself, it’s really important to have a community… So you don’t feel like you are facing the current on your own,” she says. “[So] when you are feeling really depleted, you have a source of recharge, to connections, to appreciation; to being part of a safe space where you can just process all of these emotions.”

Mr Wham thinks that pacing oneself is also important in ensuring that one’s changemaking efforts are sustainable in the long run.

“It’s important to pace yourself and decide based on your personal circumstances the types of risks you can take and the ones that you can’t, and how much work you can take on,” he advises. “Don’t feel bad or guilty that you’re not doing as much as you [think you] should.”

He emphasises the need for activists to be patient in looking for change, and to open themselves to alternative opinions: “You won’t see immediate results, but every action that we take lays the groundwork for the bigger change that is to come. Talk to different people, get their perspectives; it will also enhance yours.”

Finding gratification in one’s work is also key, as is relying on one’s community. “Activism should also be energising and fun. Don’t do it alone, and enjoy the company of your peers while you are at it,” advises Mr Wham.

Similarly, to Mr Yeo, community and emotional maturity are essential.

“They definitely need to form [their] own community support group. That’s where it also helps to have a lot of emotional maturity,” he says. “The job is not to go and be a hero and chiong all that and then die in glory. We don’t need dead heroes… Your role is just to mobilise, no more and no less.”

He believes that advocacy is a team effort.

”Do it with a group of friends… When I started Homeless Hearts, I didn’t try to do it alone. I got a co-founder then multiplied [our team],” he says. “Now we make it a rule that [volunteers] must go in twos and threes.”

The future of change

Fostering solidarity among changemakers is what Mr Wham wants to see happen in Singapore, which would reinforce the strength of advocates and activists as a whole.

“Even though we work on different issues and our initiatives are set up as single issue ones, our concerns, hopes and aspirations are similar,” he says.

He also hopes that more people will be empowered to speak out and take action for the things that they care about.

“When we speak and take action together, it strengthens our movement and our voice,” and this he adds “is especially important in an authoritarian culture like Singapore, where divide and rule has been how those in power abuse their positions.”

Adds Ms Ong: “I wish for advocacy and activism to be completely free from being marred by all this stigmatisation, [and] very, very unsavoury narratives around it.”

She also questions society’s attitude towards the term ‘activist’.

“We have no problem calling grassroots [changemakers] activists. But when we put the same term outside of the dominant political party, we’re all mired in fear, judgment and anxiety,” she asserts. “Why is the word activist so much held in pride and worn as a badge of honour in one instance, and not in others? I feel we need to question that.”

As for Mr Yeo, acting justly, being merciful and adopting an attitude of humility are characteristics that he hopes advocates of the future will adopt, as they set out to make a difference in the community.

“What is the end goal of advocacy and activism?,” he asks. “Cannot just go, ‘In the name of justice,’ you need to be merciful, and of course humble.”

At its most basic level, advocacy and activism is “agency”, says Ms Ong: “It is what your right is as a citizen, to want to be an agent of change… It doesn’t have to change the world.” Nor does it have to begin from larger actions, she posits, quoting Mother Teresa: “We can do no great things, only small things with great love.”

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.