“Sometimes we feel like mothers (or daughters) get in the way.”

That is how Sim Yan Ying ‘YY’, co-creator of the play (un)becoming, describes mother-daughter relationships.

(un)becoming is a play about mother-daughter relationships, depicting the complexities and vulnerabilities of mothers and daughters. The co-creators of (un)becoming, Ms Sim and Nabilah Said, devised it alongside actors Suhaili Safari and Chanel Ariel Chan. The play asks essential questions like “What does it mean to be a mother?” or “How can one be a ‘good’ daughter?”

(un)becoming will also be presented digitally, a reflection of our current pandemic times. On the digital medium of the production, Mses Nabilah and Sim say “we’re also very interested in how mothers and daughters communicate and miscommunicate in these times, both online and offline”, adding richness to the play.

Often when we think of mother-daughter relationships, we think of them being either “very saccharine sweet and Hallmark card-esque”, as Ms Sim describes, or being toxic and abusive. But mother-daughter relationships are rarely so simplistic.

Usually, mothers act out of concern and love for their daughters but these actions of kindness might not resonate with daughters. Daughters might want to instead rebel against their mothers to cement their independence and unique identity. During the interview, Ms Nabilah also talks about how women’s bodies and actions are constantly policed, and how that leads to mothers acting in certain ways towards their daughters and the daughters’ reaction to that.

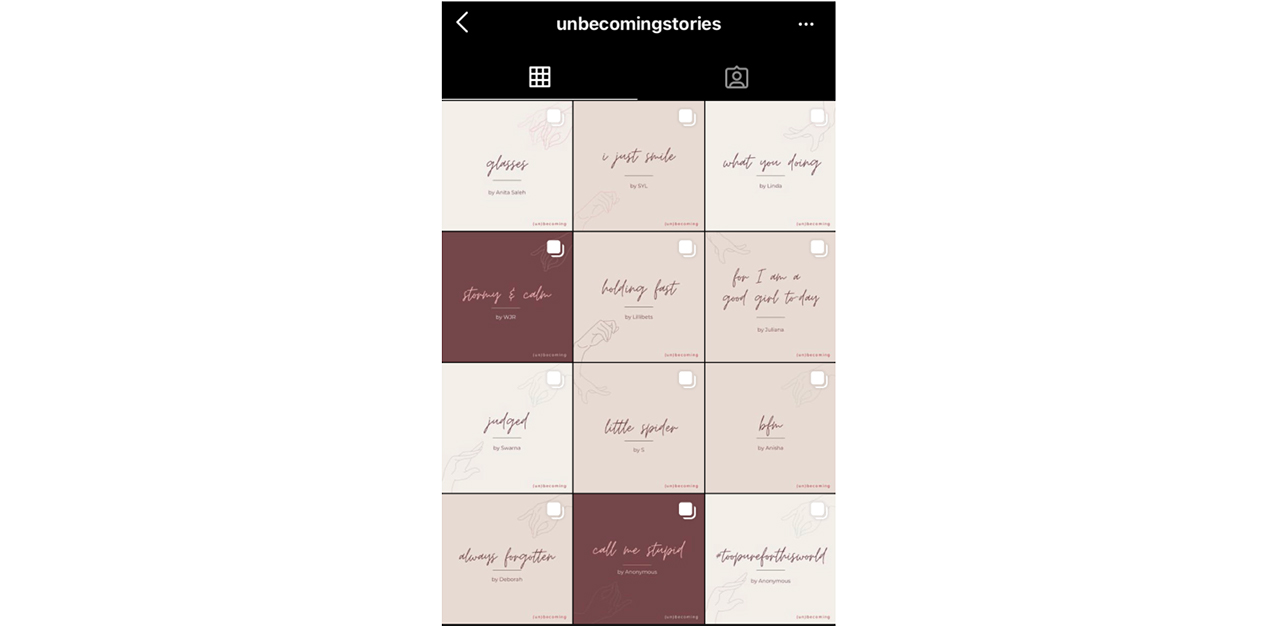

Looking at some of the stories published on (un)becoming stories, the digital exhibition that complements the play, we can see the rich and layered narratives in each distinct mother-daughter relationship.

One post reads: “I wish my daughter understood my reasons for nagging at her.” Another says: “My mum used to call me ‘stupid’ a lot” and “The way she raised me probably contributed to my depression.”

Some even touch upon how their mothers and daughters have influenced them: “My mother is a hoarder,” and “when [my partner] pointed at the mountain of clothes (I no longer wear)… the truth hit me like a lightning – I was turning into my mother.” Another writes: “My daughter helps me express myself better.” But the underlying qualities in all these different stories were love, care and admiration, albeit expressed differently by both mothers and daughters.

Studies have shown that mothers influence significant aspects of personality in their daughters, like gender identity and sexuality, careers and academic aspirations and self-esteem. Even then, most studies have also indicated that the depiction of motherhood in media is laden with traditional stereotypes, such as that of a mother staying at home to look after her children, giving many people the impression that there is only one form of motherhood that is acceptable.

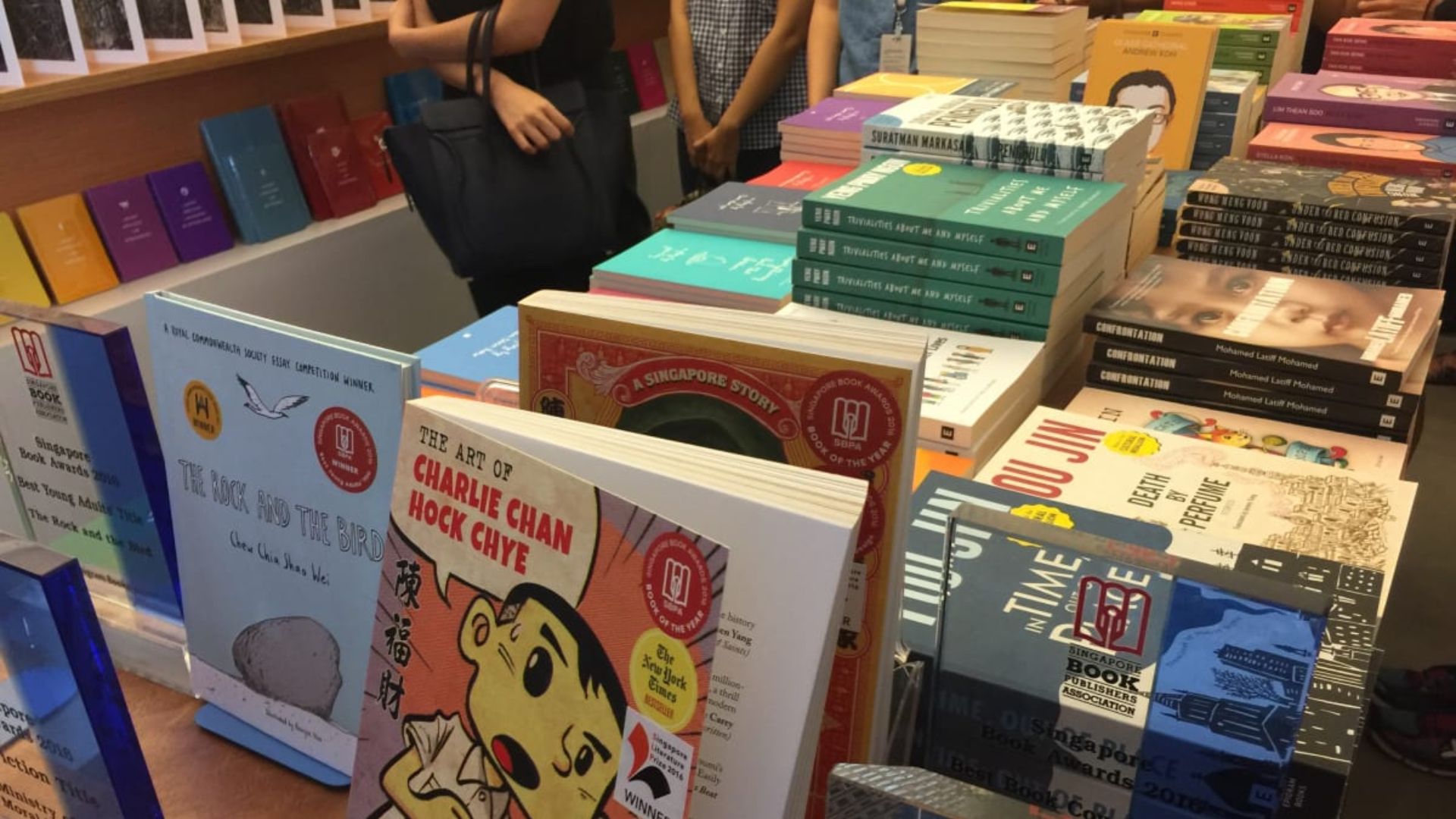

There is, however, scant depiction of mother-daughter relationships on screen. Apart from a few notable examples, such as Lady Bird or Gilmore Girls (which are both set in White, middle-class families), mother-daughter relationships remain a grossly underrepresented narrative (with diverse representation being rarer). Therefore, (un)becoming is a rare gem in theatre, representing complex and diverse mother-daughter relationships that are not usually seen on screen, or on the stage.

In view of T:>Works’ Festival of Women N.O.W. (not ordinary work) 2021, TheHomeGround Asia approached Sim Yan Ying, Nabilah Said, Suhaili Safari and Chanel Ariel Chan, to learn more about their thoughts on creating the play, around motherhood and other adjacent issues, as well as their previous works, and what they hoped to achieve from (un)becoming.

NOTE: These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Nabilah Said and Sim Yan Ying: (un)becoming conveys multiple meanings. The most obvious one is that ‘unbecoming’ can refer to how a mother might describe the behaviour of her daughter. But one can also wear that as a badge of pride, to reclaim one’s transgression amidst society’s expectations. ‘Becoming’ also conjures up images of formation or creation. And as a counterpoint, to “unbecome” can then harken to the idea of unpacking, unravelling, or detaching oneself away from an origin point. We thought that the title encompassed multiple possibilities, and is truthful to the impulses that we’re exploring in this work.

TheHomeGround Asia: Why the focus on mother-daughter relationships? Was there something you wanted to say that stemmed from the personal? Have you been inspired by other creative works that explore this relationship?

NS and SYY: We were initially interested by ideas of women ‘transgressing’ certain boundaries, and by whose standards we measure such transgression. The idea eventually developed into looking more specifically at how mothers perceive their daughters’ actions and behaviours. We then flipped it as a thought experiment of sorts – what are our mothers thinking when they do certain things or make unsolicited comments, and why do we so often take them the wrong way when they’re usually a result of love? It then grew into a piece that explored the mother-daughter dynamic in the Singaporean context.

THG: What are some reasons, in your experience, why mother-daughter relationships are so rich and complex (e.g. loving yet fraught with tension, kind and toxic at the same time)?

NS: Our research shows that mothers and daughters relate to each other and communicate in certain ways that aren’t exactly found between mothers and sons, or fathers and daughters. But there is something to be said about the expectations and insecurities that mothers and daughters have that are deeply entrenched within and shaped by the societal norms which are placed on women. Women’s bodies, words and actions are often policed, and this can feed into how a mother might act towards her daughter – even if it is for protection or done with good intentions – and how a daughter might react to that.

SYY: I think it has a lot to do with how we negotiate our identity in relation to the other. We all want to chart our own paths and find our purpose in this world, but it sometimes feels like our mothers (or daughters) get in the way… although it’s usually a result of love. And there are a myriad of other reasons as well – personality clashes, differences in how we express love (and hurt), societal expectations of what a “good” mother or daughter is, intergenerational trauma, and so on. We also don’t talk enough about motherhood that exists in other forms, when alternative mothers in our everyday lives can touch our lives just as much as, and sometimes more than, our biological mothers.

THG: Would you like to see greater representation of mother-daughter relationships in mainstream media (news, creative arts, eg. movies, books, etc)? Why and how?

NS and SYY: Definitely, especially those from our part of the world, and which showcase the diversity of mothers and daughters from different cultures and backgrounds. That’s partially why we wanted to create this piece. Currently, we see mainly Western-centric portrayals of mother-daughter relationships, or ones that are quite binary – either something very saccharine sweet or those that portray extremely negative relationships. That being said, we acknowledge that there have been shows about mothers and daughters explored in local theatre, such as Recalling Mother by Checkpoint Theatre and The Book of Mothers by Eleanor Tan.

THG: What are some stereotypes and norms about mother-daughter relationships that you hoped to challenge through (un)becoming?

SYY: We tend to see motherhood typified through conventional Hallmark card representations or boxed into categories, such as The Strangers or The Role Reversal. But in reality they often encompass multiple characteristics and complexities, and evolve over the years as well depending on circumstances and phases of life. Some things that we tried to do in this play are breaking away from presenting a certain ‘type’ of mother-daughter relationship, expanding to include non-biological mothers and daughters, and digging deep into what we inherit not just from our mothers but also from the generations of women who come before us.

THG: How does the digital exhibition, (un)becoming stories on Instagram, complement the play?

NS and SYY: @unbecomingstories on Instagram allows us to uplift a multitude of lived experiences of mothers and daughters across communities in Singapore. These stories are accompanied by screenshots that show mothers and daughters communicating – via WhatsApp, letters, and other forms – as well as their photos. Each story contains a rich, layered and complex narrative, and forms a perfect accompaniment to the more character-driven stories explored in the play.

We also received stories that represent different kinds of real-life mother-daughter relationships, from various backgrounds in Singapore. These diverse perspectives in the digital exhibition allow others to be able to read, reflect and resonate with different stories and know that it’s okay to not have the “ideal” kind of mother-daughter relationship, even if the idealised version is what we are used to hearing about.

THG: What are some conversations you would like to have with the main women in your life, after working on (un)becoming?

NS: It makes me want to talk to my mother more. I’ve also been reflecting on the idea of lineage, and thinking about the women who have come before and will come after me, and what binds us together.

SYY: Honestly… about having children. We live in such an absurd and dystopian world today, and I sometimes think about the responsibility of bringing a child into a world like this. It also scares me greatly to consider the sacrifices I would have to make if I become a mother, and the renegotiation of my personhood and priorities.

On actors’ thoughts about the characters that they play on (un)becoming and the themes that they had hoped to explore through their characters.

THG: What was one story or character you found especially relatable in the play, and why?

Suhaili Safari: I think I can relate to Rina (the teenager character in the play) because I had the same ideals: wanting to be independent and paving my own way through life. I was always fighting for major causes that deal with human rights. I even was in a band that wrote songs about it! My mother would always challenge me, saying that I should think about myself more than I should think about others but I would always fight back against it. Today, I understand what she meant, because sometimes fighting for human rights means also fighting for myself. As teenagers, we sometimes feel like our mothers do not understand us, but as we get older, we learn that they are only wanting what’s best for us. I’m just relieved that my mother was always very patient (although irritated) with me all these years.

Chanel Ariel Chan: My favourite story that I tell as my character Eggkeykey, an eternally 10 year old girl who’s looking for her mother, has got to be the one where I retell the narratives of mythological mother figures. The current narrative being that they are vicious, scary, prey on children etc. But my character meets these figures and tells their stories and brings out what is sacredly maternal about them.

THG: What are some themes that you hoped to explore with your character?

CAC: Daughterhood. Maternal ‘instincts’. Separation. Abandonment. Independence. Cutting the umbilical cord.

SS: The main theme that I hope to explore with my character Dewi (the doula character in the play) is the courage to begin again despite our childhood traumas. Research shows that the effects of trauma can ‘echo down’ from one family member to another. With Dewi, she is always trying to process why she acts the way she does and often relates it with her experiences with her mother, which often led to guilt. Another theme that relates to this courage is forgiveness. The mother and daughter relationship is sometimes bitter but I hope to explore with Dewi, how one might find lessons in this bitterness.

About their experiences working with each other, working relationships and collaboration style, as well as the dynamics established during the preparation of the show. Interestingly, three of the four interviewees had also worked with each other before, in similar capacities.

THG: Having worked with Nabilah before, what was the experience creating (un)becoming together?

SYY: I am so grateful to have Nabilah as a co-creator. There’s a lot of mutual learning involved as Nabilah comes from a playwriting background and I started mostly with directing. Personality-wise, I think we complement each other well. I tend to take charge of a room and work quickly and intensely, whereas Nabilah works with a lot of thoughtful consideration and steps in when a gentle redirection is needed. I deeply appreciate her patience, ability to view things from multiple perspectives, and the maturity and ease with which she communicates with our collaborators. It’s also been so helpful to have a partner to bounce ideas off of, talk through dilemmas, as well as share the workload (although to be honest the combined workload is more than both of us can handle!).

THG: What was the experience like collaborating with Yan Ying again?

NS: It’s been a great experience for me. We worked for the first time when I was a dramaturg for YY’s last show, “Where Are You”, a play which deals with grief. Dramaturgy was and is still very new to me, and I appreciated how YY was very generous, nurturing and communicative about the value that I could bring to the team, despite my inexperience.

With (un)becoming, I am once again doing something completely new, which is co-creating and devising a piece as a director, on top of writing the script. I’ve learnt so much from YY about how to conduct rehearsals, and direct for a devised play – and how to put together a show for Zoom, which has so many moving parts, it’s crazy sometimes.

THG: How different has it been working with Nabilah on both Inside Voices and (un)becoming?

SS: Inside Voices was an already complete script that Nabilah had written and worked on with other actors prior to Vault Festival. While we were in London, the process was conventional in that we had a director who already had a vision on how to stage the play. Although Nabilah was working in another production in Singapore, we communicated via emails as support to analyse the text. This time, since un(becoming) is a devised piece, everyone worked collaboratively to research mother-daughter relationships. Both Nabilah and Yan Ying provided a list of research materials as a jump-off point and curated specific improvisation exercises that invited actors to bring voice and body to the work.

THG: What was it like to work with everyone for the first time on something this intimate?

CAC: It is wonderful! There’s something very unique about working with a team of women. YY and Nabilah created a space where everybody is respected. The result is a non-hierarchical way of working. In a way they’ve created an equal space that is patient, non-judgmental, kind and empathetic.

About their previous works, as actors, playwrights and directors, and how that influenced the creation of (un)becoming or influenced their thoughts on (un)becoming, and on the portrayal of women’s stories and motherhood.

THG: Your previous play, Inside Voices, explored the themes of feminism, sexuality, race and religion, in the context of the #MeToo movement as well as rising Islamophobia around the world. (un)becoming explores motherhood and what it means to be a mother and daughter. Did Inside Voices influence the development of (un)becoming? If so, how?

NS: I think this reflects my interest in writing stories about women, and their strengths, vulnerabilities and complexities. But each play is completely different, and I like to honour the different journeys of each work on their own terms. When I wrote Inside Voices, I was interested to explore the Malay-Muslim female perspective especially for an audience in London – so there were also other issues at play, such as colonialism. (un)becoming is contextualised in a completely different way, and it also involves the perspectives of other collaborators in the piece, as well as the women we interviewed in the course of our research. Unlike Inside Voices, (un)becoming is a piece written for the pandemic / digital theatre age.

THG: With plays like Inside Voices and (un)becoming, we are starting to see more stories about women in theatre. How do you feel about this? Do you think that there is still more that needs to be done to improve this representation?

SS: I believe that Singapore’s theatre (especially since the 90s) has seen women directors/writers like Aidli Mosbit, Zizi Azah, and Atin Amat work to centre stories about the female experience, namely Ikan Cantik, Heart(h), and Lantai T. Pinkie. What is awesome to learn is how these directors are very well-researched and sensitive about the culture that highlights the Asian women’s perspective. I hope that younger Singaporean writers and directors can continue researching from our history, and use language that relates to their journeys as women.

THG: Both (un)becoming and some of your previous works, like ‘Where Are You?, showcase diverse experiences surrounding the same theme. Why is it important, in your opinion, to highlight diverse voices in stories?

SYY: Highlighting diverse voices, in my opinion, isn’t a choice we are given liberty to take. Diversity is simply the society we live and breathe in – yet oftentimes we fail to put enough effort into understanding the experiences of ‘the other’. I hope that the art I make can contribute towards bridging people from different communities, and allow us to discover similarities in our experiences while also honouring and challenging our differences.

THG: In the play 3 Fat Virgins Unassembled, you portrayed Virgin C, who is a mother dealing with problems such as infidelity. Given the differences between 3FVU and (un)becoming, what are your thoughts on the portrayal of motherhood in theatre?

CAC: There should be more stories on motherhood put on stage. Motherhood is such a broad and complex subject. It brings such a dramatic shift that affects so many areas of our lives, from how our brain and body changes, to our relationships and our career.

In (un)becoming I play an ‘eternal daughter’ searching for her mother. I think there’s an inexplicable bond between a mother and a daughter that’s fascinating. What happens when a mother doesn’t want to be a mother but a daughter will always remain a daughter? How much do daughters need a mother? Those are questions that I’m exploring in the play.

(Un)becoming is co-created (written/directed) by Sim Yan Ying ‘YY’ and Nabilah Said; devised and performed by Arielle Jasmine Van Zuijlen, Chanel Ariel Chan, Isabella Chiam and Suhaili Safari; with dramaturgy by A Yagnya and Cheng Nien Yuan; scenic and costume design by Johanna Pan; multimedia design by Jevon Chandra; sound design by Tini Aliman; stage management by Shivani Rajan and Catherine Ho; and filming and editing by Chimene Khoo.

Livestreamed digital performances run from 14-17 July 2021. Ticketing details can be found here.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.