It has been said that the true measure of any society’s development lies in its people’s quality of life. Weak or able, poor or rich — how free are people to make choices that are both productive and fulfilling?

In 1967, after over a decade of terminal care research and medical social work, Dame Cicely Saunders introduced the modern hospice concept through the establishment of St Christopher’s Hospice — the world’s first hospice founded on the principles of compassionate and palliative care.

Dame Saunders’ life work had convinced her of the immense value in addressing the fears and concerns, as well as palliative comfort, of the terminally ill. Her philosophy was largely motivated by the desire to maintain a high quality of life for the sickest and the dying. Embodied in the avant-garde physical environment of St Christopher’s Hospice, where patients were reportedly able to write, garden, talk and even get their hair done, it marked a distinctive shift from the conventional hospital model of Britain in the 1960s to one that resembled a home.

In Singapore, the hospice movement had its beginnings in 1985 when St Joseph’s Home set aside 16 beds for hospice care as a response to the unmet needs of cancer patients dying at home. A newspaper article about the work then brought together a group of volunteers who started a home hospice service under the charge of the Singapore Cancer Society in 1987.

Over the decades, the movement has evolved with the help of several charities, hospitals and philanthropists all sharing Dame Saunders’ philosophy — that advancing a patient’s quality of life in his final days is what a civilised society does.

Adding life to days

Unlike hospice care, which takes place after someone has stopped curative treatment, palliative care can improve the quality of life of those with life-threatening conditions, whether or not a cure is available. In the realm of palliative care today, it is commonly expressed that it “adds life to days”. Care facilities are increasingly shifting their focus away from the imminence of death and the physical aspects of caring to how one’s well-being at the end of life can, in reality, become a source of contentment and fulfilment, smoothening the transition between worlds.

Perhaps the most recent manifestation of this philosophy is Oasis@Outram, a day hospice that, much like St Christopher’s Hospice at its inception, aims to challenge society’s preconceptions of an end-of-life facility.

Developed in partnership with the Lien Foundation and designed by Lekker Architects and design studio The Care Lab to transform the experience of the terminally ill, the 900sqm space boasts chic interiors and a snazzy country club vibe. But instead of golf courses, there is a dedicated mahjong room, salon and spa, theatre and horticulture “greenhouse”. The day hospice might also be the first on the island with a fully operational bar, complete with its own happy-hour menu and smiling bartenders.

Located at the Outram Community Hospital and operated by HCA Hospice Care (HCA), the country’s largest home hospice provider, the day hospice was conceived on three pillars — diversity, dignity and development — and is HCA’s newest attempt at a conversation on end-of-life wellbeing.

“The model of care at Oasis@Outram prioritises our patients’ individuality and shifts the caregiving model from a conventional one-size-fits-all model, to one that acknowledges that every patient is a unique individual. Because everyone is different, we offer a diverse range of unique and unconventional activities and programmes at any one time,” says HCA’s CEO Angeline Wee.

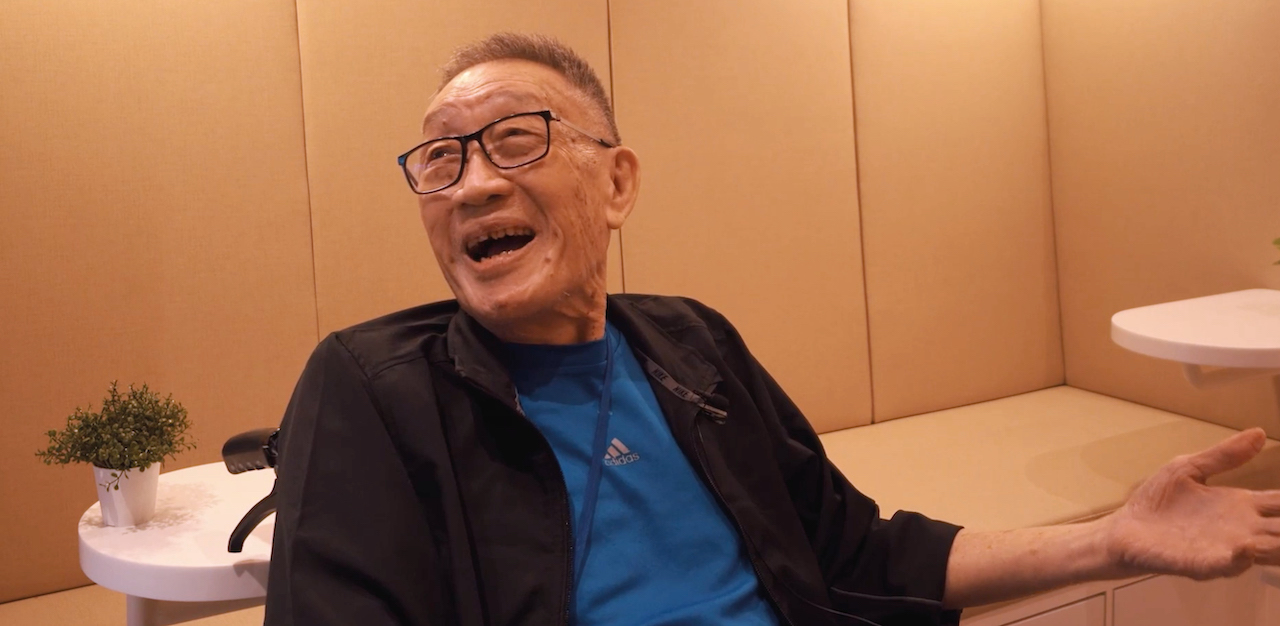

Mr Joseph Liu, an 85-year-old patient who has been at Oasis@Outram since its soft launch in July, says the hospice continues to surprise him each day with the level of attention he receives as well as the thoughtfulness that went into the space.

“This place has everything I could have asked for. The facilities and carers here are so much better than the place I was at before,” he says.

The Singapore Hospice Council (SHC), an umbrella body that represents hospices and organisations providing palliative care, recently illustrated this very notion of adding life to a patient’s final days through a short film which chronicled a young patient’s journey to host his first art exhibition at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts before succumbing to colon cancer.

An aspiring artist, Khairul managed the feat with the help of his palliative care nurse and her team from HCA, whose mission was to support the youth in “leaving with no regrets”.

In many ways, this “whole-person” care is, to the SHC, what end-of-life care ought to be and what its member organisations across the country strive to provide.

“The palliative care provided by SHC’s member organisations aims to relieve suffering and improve the quality of life of patients and their family members by caring for the “whole-person” — physically, emotionally, psychologically and spiritually — and a multidisciplinary team consisting of doctors, nurses, social workers, therapists, counsellors, and trained volunteers provide this support,” a SHC spokesperson says.

We only die once

While the quality of one’s life continues to take centre stage in Singapore’s hospice movement, not everyone shares the same view of death today. Across the developed world, the notion of a dignified death has sparked intermittent but intense debate among medical professionals, religious leaders and scholars for decades.

Similar debates have risen at home as well, with Professor Tommy Koh and Bishop Emeritus Robert Solomon’s 2014 stab at the issue being the most notable one in recent years. Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon’s speech at the Singapore Medical Association (SMA) Annual Lecture in 2013 also brought up several in depth considerations against the “right to die”.

The argument for assisted dying, which revolves around dignity and autonomy over one’s death, particularly of the terminally ill and chronically suffering, has often been refuted by arguments for the sanctity of life, the human experience, the powers of quality palliative care, and that which expose the delicate relationship between patient, medical professional and society at large.

Perhaps ironically — considering where Dame Saunders had come from — Britain is the latest nation to have reignited conversations around dignity in dying, most recently in an Intelligence Squared debate between notable academics and medical professionals.

But while compelling arguments continue to fuel these debates, the answer to the question of why the terminally ill and intractably suffering should have to endure intense pain without any prospect of relief remains elusive.

In Singapore, where almost a third of all deaths each year are cancer-induced, the barbarity of intractable suffering near the end of one’s life is far from unimaginable.

Ms Yap, a 25-year-old HR executive who only wishes to go by her last name, has seen her father’s health deteriorate rapidly over the last five years along with his autonomy and sense of dignity.

Diagnosed with end-stage nasopharyngeal cancer, Ms Yap’s father has had much of his autonomy gradually stripped away by his treatment, which has brought on muscle deterioration in the throat and mouth, making swallowing food impossible and confining him to a liquid diet.

Ms Yap adds that this weakening of the muscles also means that his speech has become exacting and almost punishing as her father can no longer speak “without dribbling or spitting”.

“No one apart from my mum and I talk to him, as they can’t understand his words or they feel bad getting him to talk because it’s difficult for him. Because he’s quite frail, and with the saliva issues, he’s had people stare at him as if he was a dirty and unhygienic person,” she says.

Apart from bodily decline and constant pain, Ms Yap says her father’s forced withdrawal from his social life also represents a huge loss of dignity. From declining to have meals with the family to avoiding his peers, Ms Yap believes that her father has “lost a huge reason to continue living”.

It was only after watching Stop The Horror, the 2017 Australian short film about the immense pain and suffering a terminally ill patient and his family are forced to endure in his last days, that Ms Yap began to entertain the possibility of euthanasia for her sick father.

“It really dawned on me how much pain and suffering my father would possibly have to go through,” she says.

A year later, after Ms Yap witnessed a friend’s mother pass from cancer, which she described as “painful”, she broached the topic with her mother.

As indicated by the SHC spokesperson, a 2019 research study conducted by the Singapore Management University (SMU) found that one of the four most important wishes of the terminally ill was to have control over pain relief and other symptoms.

While Stop The Horror may have been dramatised for effect, its premise was based on the very real experiences of countless families near the end of a loved one’s life.

Ms Leck, a senior executive in the hospitality industry who also wishes to go by her last name, witnessed her sister’s gruelling battle with brain cancer over the course of six years “without being able to do anything”.

It had started with mouth ulcers, then a urine bag and liquid diet. Eventually, Ms Leck’s sister could no longer open her eyes due to the nausea it would induce. Neither could she sleep due to the partial paralysis of her upper and lower body.

“Because she couldn’t toss and turn, her body was stuck in the same motionless position, but in a lot of pain. Nobody could sleep like that,” she says.

Recounting the times she spent by her sister’s bedside watching her endure what must have been excruciating pain and discomfort, Ms Leck says all she could do was tell her to seek comfort from God.

“Towards the end of her life, she actually told me she didn’t want to hold on anymore and asked if I could help. I just cried.”

About three weeks before her sister’s death, the family decided to stop the life-prolonging medication she had been on in their previous attempt to “hold on”. The doctor’s prognosis: It would take a month before her organs begin shutting down.

“There was nothing I could do for her in those six years, that was the hardest part. I just wanted her suffering to stop, for her to go peacefully,” Ms Leck says, tearing from the memory.

The difficulty with a dignified death

Despite traumatic tribulations such as these, most Singaporeans seem clear on how they feel about assisted dying. In his 2014 debate with Professor Tommy Koh, Bishop Emeritus Robert Solomon’s primary argument against the right to die — that one’s freedom to choose ought to be trumped by the sanctity of life — won him 65 percent of the vote.

“…the right to life cannot be extrapolated to the right to die. Life is sacred and one does not have the freedom to take one’s own life, no matter what the extenuating circumstances might be,” the bishop said in 2014.

In many ways, the sentiment expressed by the bishop is closely related to the fear some Singaporeans harbour about the potential ramifications assisted dying may have on society’s relationship with itself.

Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, in his 2013 speech, alluded to this in a quote from Baroness Campbell’s 2006 note published in The Guardian: “Assisted dying is not a simple question of increasing choice for those of us who live our lives close to death. It raises deep concerns about how we are viewed by society and by ourselves.”

But while such views remain prevalent across Singaporean society, there is reason to believe that a more liberal consensus is emerging. Between 2018 and 2021, more than five discussions on euthanasia have sprung up on Singaporean subreddits, while The Straits Times and the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) discovered in a 2019 survey of 19-year-olds that only 14 percent disagreed with potentially legalising euthanasia.

Ms Yap is of the view that such differences in attitudes stem from religious beliefs and insecurities about one’s value and place in society.

“I think the crux of such arguments is a difference in understanding between the older and younger generations. The former faces concerns of being obsolete, irrelevant. So I think they’re extrapolating such fears onto the topic of euthanasia,” she says.

“Particularly in the case of euthanasia, there are a lot of religious considerations, and generally the government stays away from potentially touchy topics. This automatically limits the range of topics that are discussed at society-level.”

To the contrary, Ms Yap believes that euthanasia would create healthier attitudes around death, allowing Singaporeans to come to terms with the inevitable.

“I know for a fact that it would put me at ease knowing that, if anything happens, I can be promised a painless death on my own terms.”

Recent developments in the realm of palliative care have, however, signalled that the government might finally be open to these tough conversations.

Speaking about having open discussions on death at the virtual two-day Singapore Palliative Care Conference on December 9, Health Minister Ong Ye Kung said: “It’s probably the most important thing we need to do. It has to happen within families, between patients and doctors, and among members of society and the healthcare fraternity.

“It is one way to bridge the mismatch of expectations and desires between a dying patient and his or her loved ones.”

But wherever society is headed, Ms Yap believes it is inevitable that the concerns around pain, suffering and dying will become increasingly pertinent in an ageing society such as Singapore’s. This naturally means that quality palliative care will remain vital in the end-of-life conversation, and that hospice concepts such as HCA’s Oasis@Outram may eventually become the norm.

“We see great potential in adapting this model — in part or in whole — for other daycare facilities, as we are seeing some initial success with the feedback from visitors, patients and their caregivers. The ethos of our care model is also consistent with the general industry shift towards looking beyond caring for patients physically, to ensure that there is also quality of life,” HCA CEO Ms Wee says.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.