‘F*** off’, ‘Useless Doctor!’, ‘You shouldn’t be a doctor’, ‘If I were in my 50s, I’d rape you’. These are examples of abusive statements hurled at junior doctors by the patients they serve. Such remarks might have gotten most human resource personnel involved if it were in another setting. But, in the medical sector, these situations happen so frequently that most doctors simply shrug them off as “just another day in healthcare”. Despite facing unreasonable behaviour from some patients and caregivers, most junior doctors are motivated to stay the course, and to continue to have their patients’ best interests at heart.

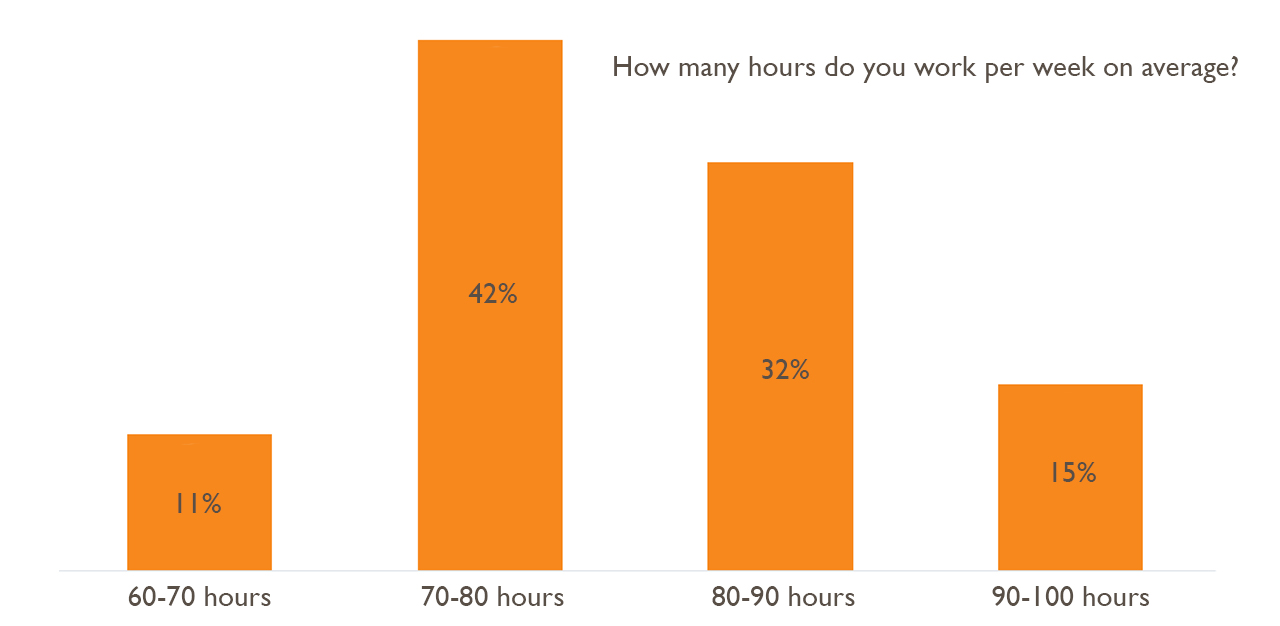

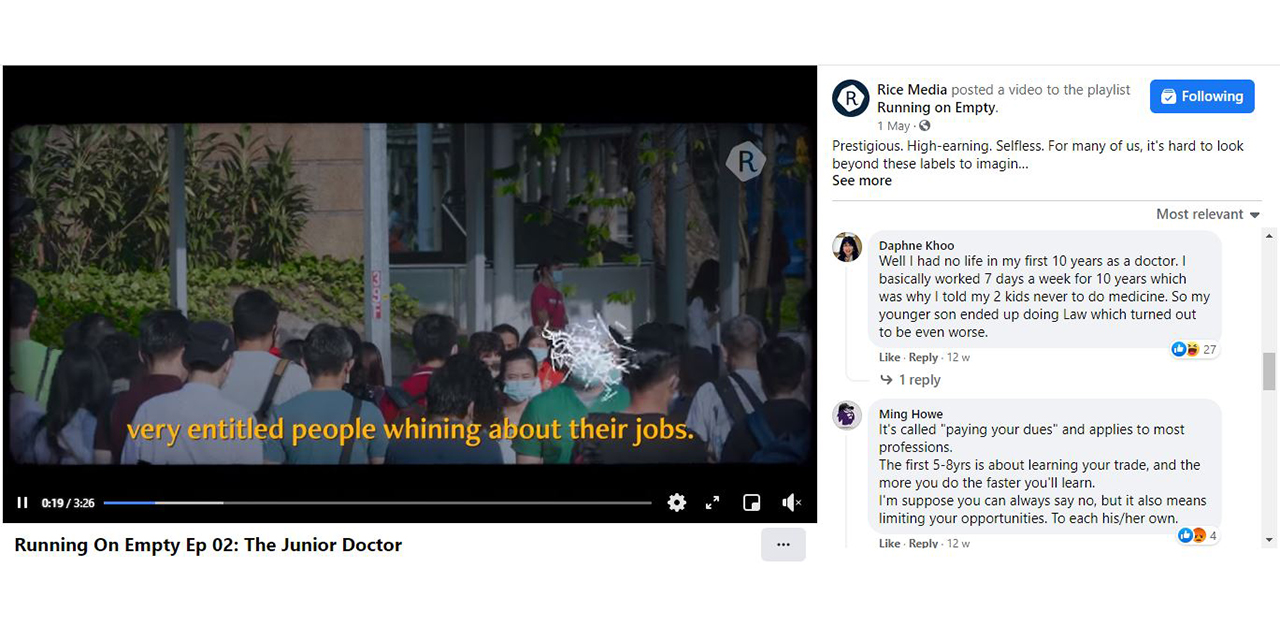

TheHomeGround Asia was curious to find out more about what doctor’s lives were like, after Rice Media published a video interview with an anonymous junior doctor about his working conditions. The interview revealed some little-known facts about the lives of junior doctors, such as working as many as 100 hours a week, the irony of not having adequate nutrition but instructing patients to have a healthy diet, and apparently earning less than a person working at a bubble-tea shop. Most people who commented on the video were sympathetic, while others criticised the doctor for whining.

Was it simply this doctor’s personal experience and poor luck, or a fate that most junior doctors silently accept and endure, as part of their commitment to their job?

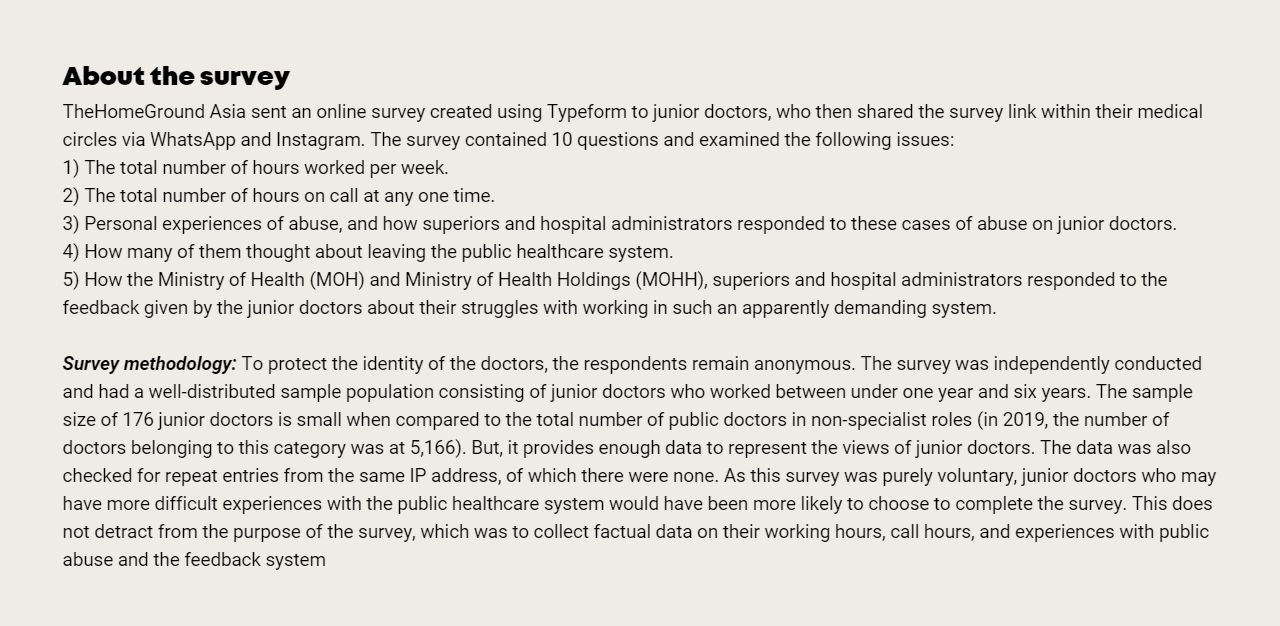

To get some answers, TheHomeGround Asia conducted a survey in May, reaching out to junior doctors in Singapore’s public health system. The questions were completed anonymously, as a general fear exists among junior doctors about the potential backlash and negative consequences they might face for criticising the system, which could affect their careers.

Within three days, 176 junior doctors (house officers and medical officers) completed the survey.

The data collected reveals that the experiences of the junior doctor featured in the aforementioned media interview were not unique to him.

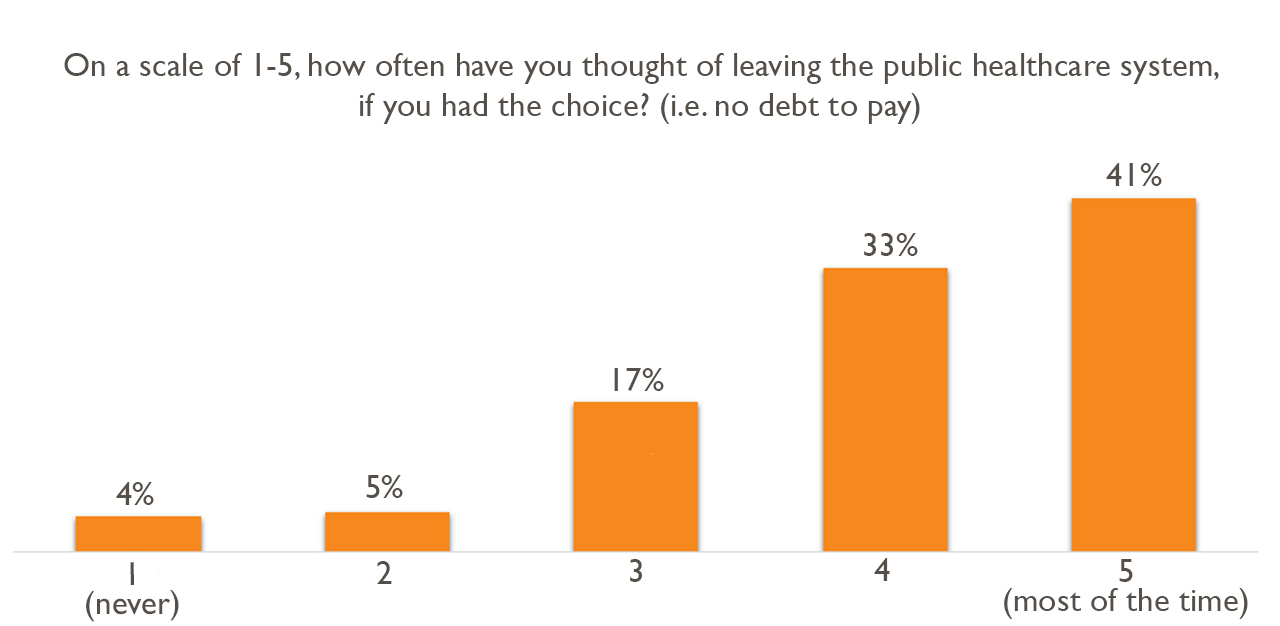

Of the survey responses received, the starkest was that 73.8 per cent (who answered ‘4’ and ‘5’ on a scale of 1 being ‘never’ and 5 being ‘most of the time’) of junior doctors have contemplated leaving the public healthcare system, if they had the choice.

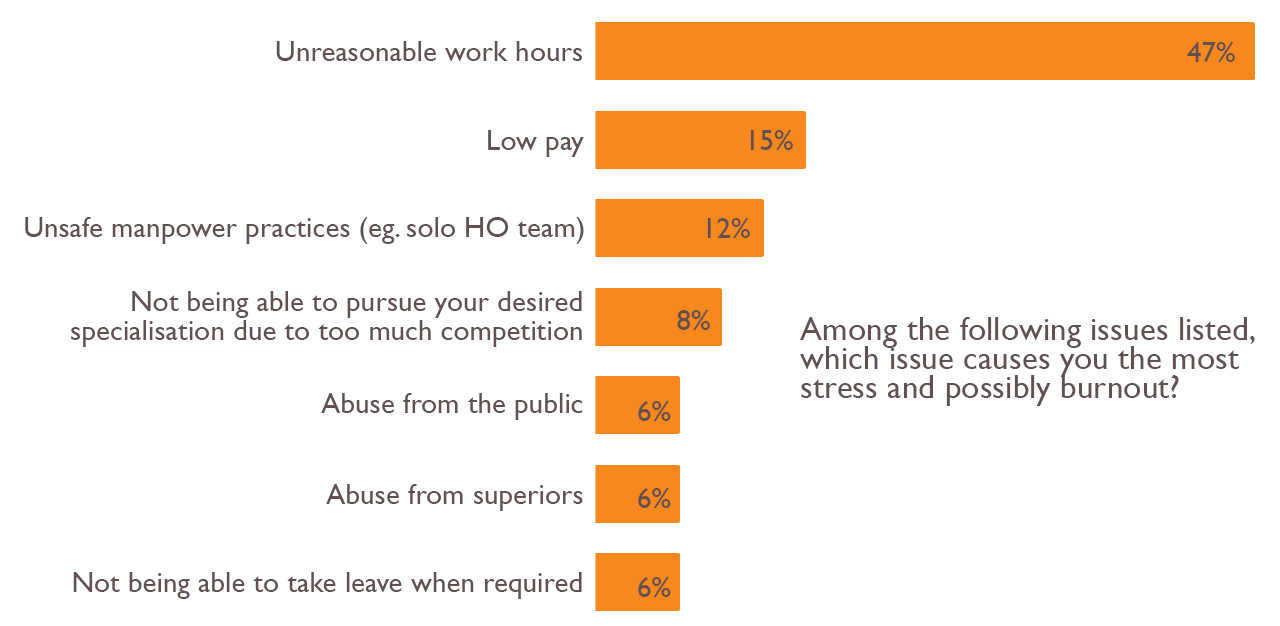

When asked what the biggest stressor and cause of burnout was (that may influence their decision to leave), only 6.2 per cent of doctors attributed it to public abuse.

Over two weeks, we spoke with 10 doctors via Zoom, who comprised those with between three months and four years of work experience, of whom two had left public healthcare. We were also in touch with three more doctors, who shared their stories with us over Instagram and text messages. These sources were in slightly more senior positions, with almost seven years of experience, and were either residents or doctors who had left to join the private sector.

Based on these additional conversations with junior doctors, residents and those who had left the public healthcare sector, and the survey’s results, what were the primary reasons to contemplate leaving the public healthcare system, as soon as possible? Even if it meant relinquishing medical careers, after dedicating nearly 10 years of their lives to getting licensed?

‘Just part and parcel of this job’: Abuse from patients not pressing enough reason to leave

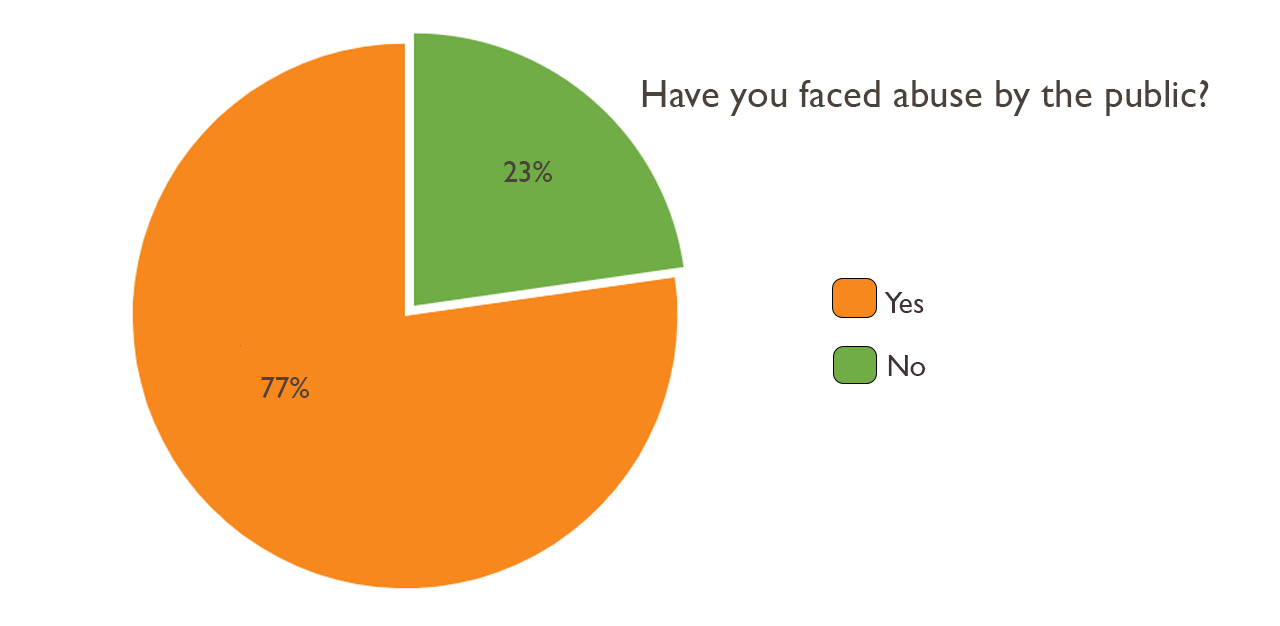

Abuse from the public appears to be commonplace. Of the 176 respondents, 77.3 per cent indicated that they have been on the receiving end of verbal and physical abuse from patients. Other junior doctors have also faced physical and sexual threats. One shared that a patient “peed on [me] deliberately”, and another had to fend off a patient who “tried to kiss me while I was on call.”

Given how frequent these incidents occur, many doctors shrug the abusive behaviour off as “another day in healthcare”. While some recall being told by seniors that “it’s just part and parcel of this job.” Many of these doctors stay on, determined to fulfill their pledge to serve humanity to their best ability, and with their patients’ best interests at heart.

Reasons enough to quit

Reasons enough to quit

So if not patient abuse then what?

What were the top three reasons driving junior doctors to walk out of the public healthcare system as soon as possible, even though they still want to do their best to serve the public?

According to our interviews with the 10 doctors, and the qualitative analysis of the survey responses from junior doctors who answered a ‘4’ and ‘5’ to the question, ‘How often have you thought about leaving the public healthcare system,’ these three reasons came up the most often. They are: unreasonable working hours, failure of current feedback systems and having valid concerns dismissed by those in management positions.

(NOTE: All names for interviewees’, unless stated, have been changed to protect their identities. They had agreed to speak to TheHomeGround Asia on condition of anonymity for fear of a possible impact on their career prospects.)

Reason #1: Unreasonable working hours

Dr Terry, a fourth year junior doctor, recounts a horrific experience in his junior years.

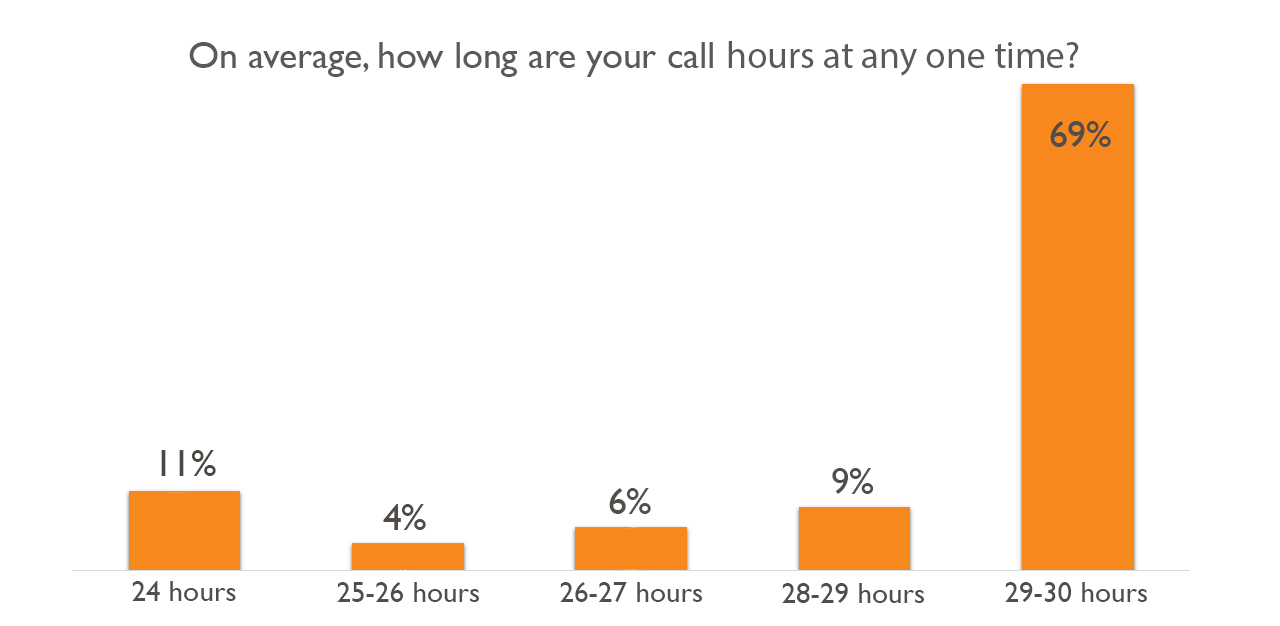

Still donned in his scrubs and a N95 mask at 7.45pm on a Monday evening, and resting in a small room at the hospital after a long day at work, he shares, “Imagine being on a 30-hour shift from Monday morning to Tuesday afternoon. Coming back to work for a full shift on Wednesday, and repeating this 30-hour cycle from Thursday to Friday. I remember having to work for 21 days in a row, and being so constantly tired it affected me both physically and mentally.”

Dr Heon, concurs with Dr. Terry about how difficult it was to work such demanding hours.

In stark contrast to Dr Terry’s hospital environment, she was at home, trying to soothe her fussing baby in the background. Dressed in t-shirt and shorts, Dr Heon shares that she had decided to leave the system altogether, even before getting her full licence.

When asked what it meant to her having to make that decision, she answers with a quiet confidence: “I was doing quite well on the surface. After working for a few months as a house officer, I took a few weeks break,” she explains candidly, noting that before the holiday, she had not realised the toll her job had taken on her life, and her personhood.

“I just couldn’t complete my calls. I would break down in the morning of the second day [during a 30-hour shift]. I would just be so tired, and I want it to stop, but the calls [from the nurses or patients] would just keep coming,” she says, “and my to-do list goes up from one to 40? And I would go to the toilet and cry. I’ll text my husband as I’m crying. And even as I felt like I couldn’t do it anymore, cannot also must can, right?”

The rigorous hours had driven her to depression and created intense anxiety, reveals Dr Heon, which led to her eventually seeking psychological and psychiatric treatment. With a horrified look on her face, she recalls how the psychiatrist at the hospital where she was working had offered to prescribe her benzodiazepines to take when on call.

According to WebMD, benzodiazepines are anti-depressants that “act on the central nervous system, produce sedation and muscle relaxation, and lower anxiety levels.” When Dr. Heon showed us the medication prescribed, it came with a warning: “Caution: This may cause drowsiness. If affected, do not drive or operate machinery.”

She says, “I started getting a bit freaked. She [the psychiatrist] said, ‘Don’t worry, you won’t fall asleep. Because you’re so anxious.’ At that point, I was afraid. I kept thinking, ‘What if I do something wrong to a patient at this point in time [if I’m on medication]?’”

Faced with these looming fears, Dr Heon decided to quit, which meant not only having to find other ways to serve out the remainder of her bond (for most Singaporean medical graduates, a five-year bond translates to approximately S$889,817* (US$653,530)), but she also had to sacrifice her dreams of being a doctor. Although she now works in a government-related industry, finding a job was not an easy process, and it took quite a few months to finally secure one.

“It’s not easy to find a job when you have a medical degree,” she states. And added that the experience was particularly traumatic, because not only was she expected to find a job on her own, without any help, her employer, Ministry of Health Holdings (MOHH) was sending her e-mails asking if she had secured a job, which compounded the pressure.

With a tired smile, she says, “I think when I chose medicine, I really expected to do it for the rest of my life. When I made that decision, I was full of grief, full of anger, full of so many emotions. Even now, I think about it almost on a daily basis. That’s how big of an impact it had on me.”

When she submitted her resignation and raised her concerns to MOHH, Dr Heon says that the Director of Healthcare Manpower had empathised with her struggles, and highlighted in an e-mail reply that this was simply “part and parcel of what it means to serve as a doctor in public healthcare.”

Given the extraordinarily long working hours for junior doctors, Dr Heon is not alone in choosing to protect her mental health over remaining in Singapore’s public healthcare system.

Wanting only to be referred to by his last name Dr Tan, who graduated from a medical university in Australia, also made a similar decision. After completing his degree, he returned to Singapore to work in the country’s public healthcare system, which he believed would also allow him to spend more time with his family. But, he soon found that this was impossible to do, given the unsustainable hours.

Speaking from Australia, where Dr Tan moved to earlier this year, he recalls clocking 14 to 21 days straight as a house officer in Singapore. Resonating with Dr Heon’s experience, he shares, “I was so tired. It caused me to make mistakes at work. I remember in my [case] notes [for a pediatric patient], I accidentally wrote D4 antibiotics instead of D5, and got reprimanded severely for it.”

With an ironic laugh, Dr Tan describes an episode when the only way he had managed to get any rest was to pass out from exhaustion: “The longest stretch I had was 28 days. I had to work both Saturday and Sundays, with my hours being from 5am to 5pm the next day, with no break. The only break that happened was when I collapsed while typing during the morning rounds.”

He elaborates, “I just blacked out because I was just too tired. I didn’t sleep throughout the night. The babies were unwell and they wake up at night. If they come in and are admitted with suspicion of meningitis, I have to take blood cultures, put in a catheter, and a lumbar puncture for the kid. And if you ever try and do that on a squirming young kid, it takes two hours each time and if I get four patients, which is a small amount, I’ll have no time to sleep on top of that.

“I was really working non-stop. No break, didn’t eat that day. Just type halfway and passed out while looking at the computer. And then 15 minutes later, my MO [medical officer] said, ‘Oh, you have enough rest already. We have to prepare for the rounds before the reg[istrar] comes.’”

Despite being close to completing his housemanship, having served for 11 months, and having received good evaluations from his colleagues at every posting, Dr Tan says that he was struggling with burnout and poor mental health.

In his final hospital posting, he reached breaking point: “On my birthday, I was also offered a position at an Australian hospital. When I received the e-mail notifying me that my Visa is approved in January 2020, I decided to resign [on the spot].”

Shares Dr Tan, “I am doing so much better in Australia. I work 76 hours in total fortnightly, and was also awarded an outstanding achievement in my first term. Many of my [doctor] friends in Singapore are struggling mentally. I had to counsel my friend who had suicidal ideation, all the way from Australia. I am trying to help my friend to move to Australia instead.”

A window into the mind of a junior doctor in Singapore who is facing burnout. (Gif source: Reddit)

Regulation of working hours

In Singapore, employees are protected by the Employment Act (Part IV) set out by the Ministry of Manpower (MOH). It states that workers “should not be working more than 44 hours per week.” But, this does not cover doctors as they are considered “managers and executives.”

Instead, doctors’ hours are regulated by the Singapore Medical Council (SMC).

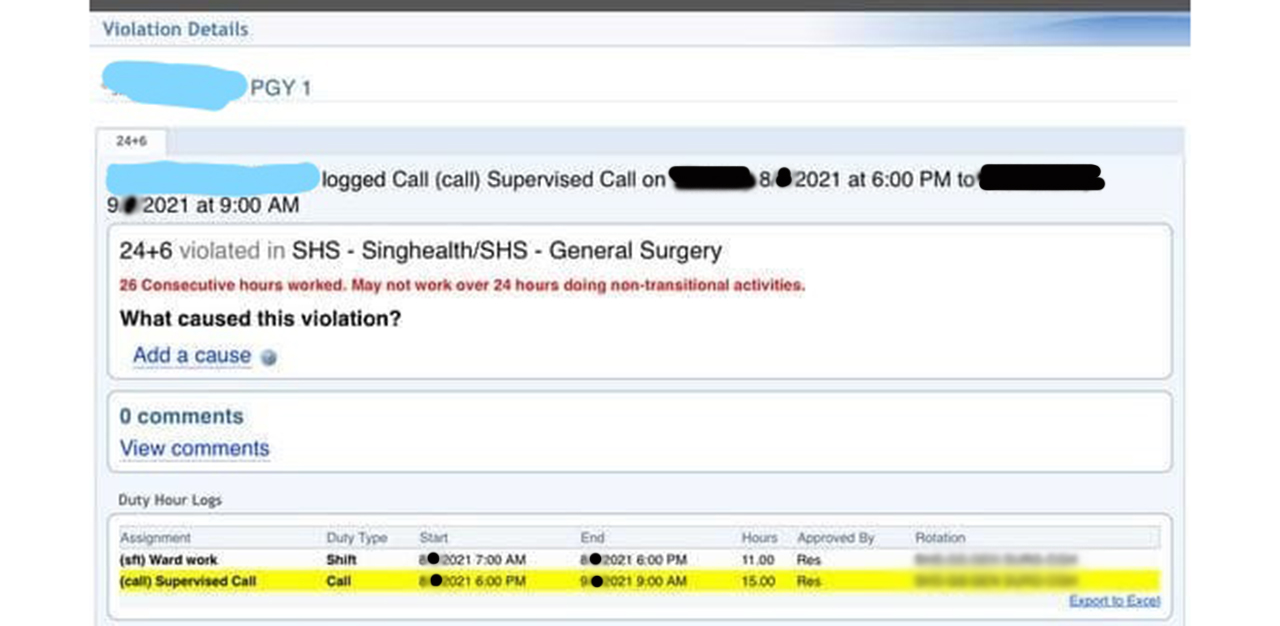

In a written reply to Former Nominated Member of Parliament K Karthikeyan, in 2015, on the working hours for housemen. MOH, together with SMC, stated that “work should not exceed 80 hours per week”, and continuous night shifts should not be longer than 24 hours (excluding an additional six hours for handover to other colleagues).

The numbers here are striking – even with the regulation, doctors work almost twice the number of hours compared to the regular employee per week, and the continuous shift hours are also more than twice that of other types of shift work. In fact, with the regulation stated above, doctors can be legally asked to continuously work for 30 hours at any one time.

Responding to queries about the survey results, MOH referred TheHomeGround Asia to a forum letter reply dated 12 July 2019 explaining the guidelines that are in place for the well-being of doctors. It had written that “doctors should work at a sustainable pace for them to perform optimally”, as this also “reduces the likelihood of medical errors.” It also notes, “Doctors are not necessarily working continuously for 24 hours within an in-house duty stint, and if there is opportunity to rest, there are facilities they can use.” And acknowledges that while public hospitals take measures to ensure their doctors “are not working excessive hours”, the “nature of healthcare means that there will be occasional periods where doctors do work over extended periods even at senior levels.”

MOHH was also approached for comment before publication of this story, but did not reply to queries relating to the survey results.

New Innovations: A system to regulate hours

New Innovations: A system to regulate hours

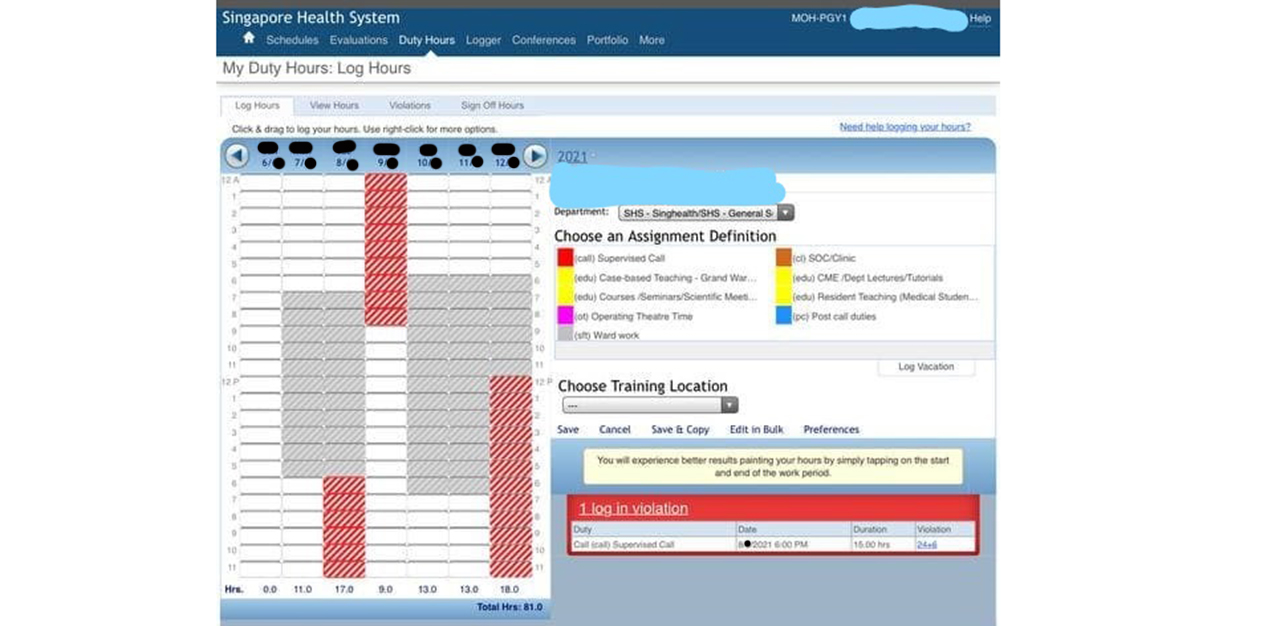

According to survey respondents, there is a system in place called New Innovations, which regulates doctors’ work hours. Various sources have confirmed that only house officers and residents are required to log the number of hours worked per week. For MOs, there are currently no regulations in place, and they form the bulk of the manpower in Singapore’s public hospitals.

Of the 42 per cent of doctors who responded that they work within the hours allowed, many cite having good medical officers, registrars and consultants within their teams, who would take on the baton and encourage them to leave before 12pm (post-call). Unfortunately, this experience was not consistent across hospitals, and appears to be luck of the draw.

‘The hospital never sleeps’: Logging hours above the regulated threshold

Three survey respondents report that they were asked to adjust their work hours by the hospital administration to ensure that the data sent is within the regulations.

Dr Paul, recalls, “MOHH got PGY1s (post-graduate year ones) to log in our weekly working hours – some of us were later told by our HODs (heads of department) to readjust their hours, as it had exceeded the ’65-70h/week’ threshold.”

Dr Tan concurs, “When I was in NUH, you had to provide reasons for working above the allowed hours. Somebody e-mailed me from the hospital admin to stop charting my hours.”

This experience has left many doctors feeling like “spare manpower, whose propensity for altruism is exploited,” says Dr Lim.

Joining us on the call from the bus home after work in the evening, he laments, “Many of us come in with the noble intention of helping people. However, we are expected to help no matter what, even if it means sacrificing our mental health,” he says. “We have to do postings that we may not want to do, every six months. The system doesn’t break down – the hospital never sleeps, right? The system doesn’t break down, but the doctors do.”

Some doctors have voiced their concerns to their superiors, hospital administrators, and their employer, MOHH. In fact, MOHH has an official whistle-blowing channel for doctors to highlight problems of excessive hours, under Violations of Policies, Laws and Regulations.

Unfortunately, all the doctors who submitted feedback indicate that the responses they received often fell into the following categories: accusations of personal inefficiency; manpower constraints; rerouting the doctors back to their own teams to settle it internally; and being told that it is “part and parcel” of the job.

In fact, Dr Barry, a fourth-year resident who previously worked in the National Healthcare System in England, shares that Singapore’s system often results in doctors simply not logging the actual hours they work. This had consequences on those who did accurately reflect the hours they worked, as it then gets perceived as an issue of personal inefficiency. In his first and second year, he was told, ‘You’re not resilient enough. You’re not efficient enough.’

“This was so demoralising,” he says, “you start doubting yourself as well, especially as a new junior doctor.”

Reason #2: Failures of the current feedback system

Most junior doctors are under a system by MOHH, called MOPEX (Medical Officer Posting Exercise). All medical officers have to fulfill a six-month posting in different departments and hospitals. After each posting, they are required to fill in a feedback form. Other than this avenue to provide feedback, channels are largely informal – junior doctors either speak to their seniors and/or consultants.

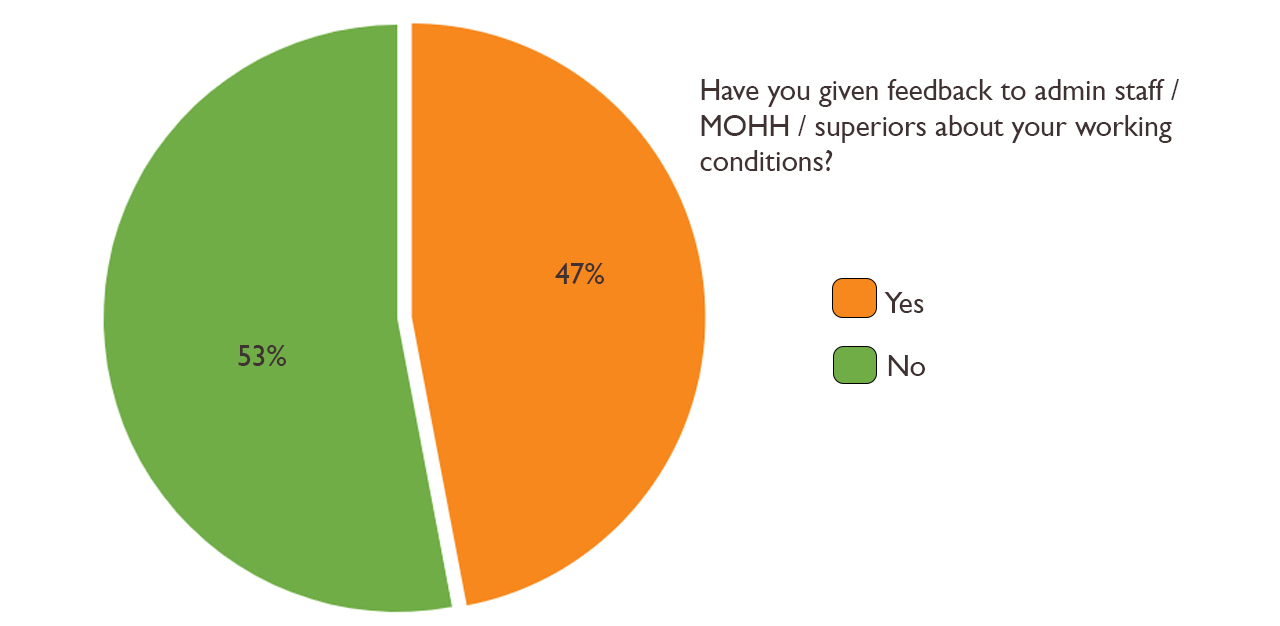

Only 47.2 per cent of doctors in the survey say that they gave honest feedback about their working conditions.

When asked why this was so, given that none of their experiences and struggles were against the law, Dr Terry explains, “Many doctors are afraid of giving feedback as it might leave a black mark on them and prevent them from getting into their desired specialisation.” Dr Chan, agrees. He adds, “Also, why would you give feedback to the same people who are responsible for your final pass/fail during your HO year?”

Despite giving feedback, 34 junior doctors reported that they had not received a response from MOHH, or administrative staff.

The doctors who did hear back from their superiors or attended closed-door dialogues were often told that “it was worse last time”. This caused many of the junior doctors to feel disillusioned with their jobs – it was not for lack of resilience, perseverance, or trying. They simply wanted to do their jobs better, with safer working conditions.

But the feedback system is not completely useless, acknowledges Dr Terry. For instance, it has produced slightly better working conditions since he was an HO, three years ago. An example he refers to is the increase in an HO’s starting salary, from S$3,500 to S$4,000 (US$2,945).

He cites another internal example: “The senior staff in an extremely busy department came down hard on the roster planners, when it came to light that one HO had not been given his one rest day in a seven-day workweek,” he says. “In another department, the roster has become micromanaged to the point where call staff are off-duty from 8am, and weekend rounds are assigned by the department, rather than negotiated within teams.”

Much of this, though, is dependent on whether the doctor is posted to a department that cares for its staff.

Dr Evelyn was motivated to write to MOHH through the official whistle-blowing channel about the hours and workplace harassment she faced, especially after a kind senior doctor in the private sector bought over her bond of S$300,000.

MOHH responded acknowledging the limitations: “Some department/organisational culture is entrenched and is a challenge to change,” it wrote. “However, MOHH and the institutions are aware and taking action to change things one step at a time.”

Although MOHH has shown in some cases to take steps to address doctors’ concerns, often the lack of timely responses to address feedback has resulted in mistrust, and the perceived failure of the feedback system.

The survey’s data reveals that those who provide feedback are more likely to leave, especially when they feel that their feedback is not heard, not taken seriously, or has no impact on changing their working conditions for the better.

Reason #3: Concerns dismissed as characteristics of ‘snowflake’ generation

Last but not least, many junior doctors want to leave because of the hopelessness they feel when trying to make the system better. Most seniors and doctors in upper management often retort that “it was worse” back in their time when given suggestions on how to improve things. Dr Terry reveals that he was particularly disturbed by senior doctors’ responses to the Rice Media interview.

“I was angry and appalled,” he says. “Here we have a junior who had the courage to blow the whistle on these inhumane practices going on in the hospital. And instead of nurturing responses, we have these very, very senior doctors gaslighting us instead, calling us ‘snowflakes’ for not being able to take these 100-hour workweeks,” and adds, “Just because they went through it, why can’t we work together to fix it?”

Are senior doctors right in their assessment of these “snowflake” doctors though? What drives their attitude towards such concerns raised by their juniors?

A senior resident who wishes to remain anonymous shares her thoughts. Having been in the public healthcare system for more than 10 years, she says that it is true her colleagues and her have worked much harder than the junior doctors of today.

“Despite having two undergraduate and one post-graduate medical school, juniors complain that the hours still suck,” she says. “When I started work, there were only two medical schools, and both with smaller class sizes than today. So we were doing more compared to them now, because we had fewer people”.

But, she agrees that the system can be improved: “There is a pervasive culture amongst senior staff that if they have suffered through something and survived, the juniors can do it too,” she says. “So it is rare to find a senior willing to step down to ease call loads, for example. The unwillingness to change keeps us all stuck in a rut.”

Junior doctors lack resilience: agree or disagree?

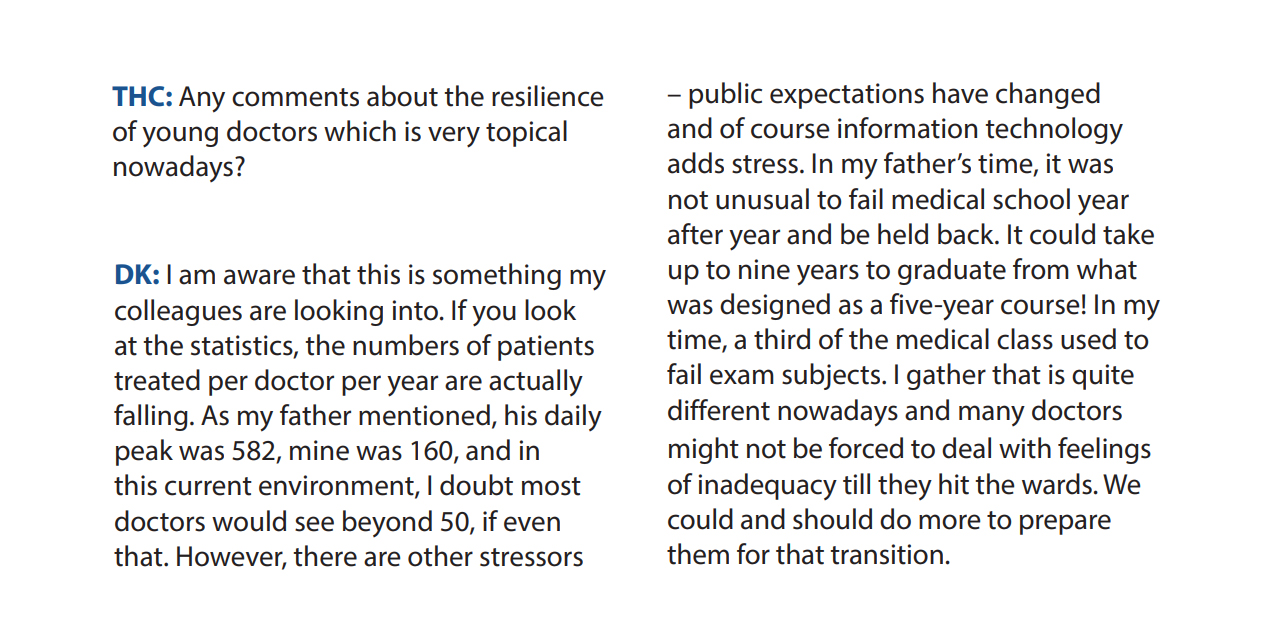

Senior doctors might see the concerns brought up by junior doctors as invalid, because of the presumption that the workload has significantly decreased since their time. Next, there seems to be an assumption that passing medical school examinations is much easier now than before. This perception might fuel unspoken beliefs that the doctors of today are not as equally qualified as the doctors from their cohorts.

An interview with MOH Deputy Director of Medical Services (Healthcare Performance Group), Dr Daphne Khoo, in 2019, that was conducted by the Singapore Medical Association might also reveal some attitudes about the question of resilience.

While Dr Khoo does not explicitly state whether she thinks young doctors are resilient or not, she notes that the number of patients treated per doctor per year has fallen, since her earlier days as a doctor. She also says that many doctors “might not be forced to deal with feelings of inadequacy till they hit the wards.”

Is this true of all junior doctors from, what cynics have called, the ‘strawberry generation’, though?

In response to the excerpt above, Dr Terry debunks the numbers regarding how many patients one junior doctor sees, per day.

“Orthopedic clinic sees 60 to 80 patients per consultant,” he says. “Our clinics can be so packed, especially for the spine, foot, and ankle services, that it’s possible to still see patients through the two-hour lunch break, take 10 mins to gobble up a bun ‘lunch’, and carry on until 7pm.”

Would being paid more make things better?

The junior doctor interviewed by Rice Media candidly shared about the moment he realised that he earned less than a staff member running a bubble tea shop. Drs Terry, Chan, Lim and Barry all agree that they would appreciate receiving a higher salary for the amount of work that they do. Most of them voice that it would help if their pay was increased from S$15 to S$18/hr, which would help to cover the cost of living comfortably, and pay off their student debt.

But, Dr Chan notes that being paid more “can only make up for the hours to a certain point”, because he says that in the end, nobody wants to do 36-hour shifts, when they can get at least $120-180/hour working as a locum in the private healthcare sector, without doing calls.

Chiming in, Dr Lim says, “I guess we could look at MOM’s guidelines for overtime pay [if we want to decide what is fair remuneration]. Not that anyone would want to do a call for the amount paid, but it is at least fair.”

Posits Dr Chin, “Ultimately it’s the culture, and the culture here is kind of work hard culture and the harder you work the better it is. The more painful it is the better. I think that has to change. I think money can only bring us so far. Being underpaid is not really a big issue either.”

Struggles of junior doctors ultimately affect patients

The junior doctors TheHomeGround Asia spoke to weigh in on two important aspects that would affect patients in Singapore.

Manpower crunch at public healthcare hospitals and clinics

If such practices continue, opines Dr Chan, more and more doctors would leave the system. To concretise how this might affect the individual seeking care at public hospitals, he shares a personal example of serving patients.

Still in the midst of completing his shift and wearing personal protective equipment, he attempts to speak as clearly as possible through an N95 mask: “I remember doing a night call and I had to admit 10 patients. I was at patient number four, and the nurse called me angrily, saying, ‘You haven’t seen my patient yet! It has been two hours!’ ‘Yes, I know. But I’m the only doctor around. Two other patients required urgent attention in between, and there are more admits. If it’s not life-threatening, you have to wait.’”

Another point they note is that junior doctors form the bulk of the manpower in hospitals, alongside nurses. And with fewer doctors available, Singaporeans could expect to wait longer to be served, while healthcare costs might also rise, in order to fill the manpower gap.

Quality of patient care

Next, the quality of patient care is directly affected by the doctor’s ability to make good and sound decisions. Junior doctors serve most of the public who come into hospitals. Many of them work 30-hour shifts. If a professional employee is already tired after a regular day’s work of between nine and 12 hours, imagine how much more fatigued junior doctors would be during a long stretch.

“Mistakes don’t happen often. But when they do happen, they can be very fatal,” shares Dr Tan.

Agreeing, Drs Lim and Chan add that being a doctor is a “physically demanding job”. Furthermore, Dr Lim expresses that “dubious decisions have been made as there’s just too much to do.”

Junior doctors want out, can we blame them?

Of all the things junior doctors have to face, what drives them out of the healthcare system the quickest is the apparent lack of care for their own well-being. The survey reveals that although they were hurt by the abuse they received from the public, this did not come up as a major factor in their consideration to leave the service. This revelation alone shows that the majority of junior doctors remain steadfast in their desire to serve and care for the public, even if they are unappreciated and maltreated for simply doing their jobs.

Many junior doctors, however, want to leave the public healthcare system for the three systemic issues stated above. In fact, what the data reveals is that these junior doctors set out to do their job well, but feel disempowered to do so in a system that makes unreasonable demands on them, dismisses their concerns, and inadequately responds to cries for help to make things better.

If these are not adequately addressed, should the country be surprised that its public healthcare system lacks manpower?

At the end of the conversations, doctors were asked what changes they wanted to see:

“I want the system to be better for my doctor friends. Many of them struggle with mental health and suicidal ideation. They shouldn’t need to choose between their mental health and their jobs.”

“I want the system to be restructured – if countries like Australia can operate on a float system or shift system, why can’t we do it too?”

“I want people to understand the reality of our work as doctors – we are working under the guise that we are the heroes performing as intended. However, that is a problem because it hides the fact that we are short on manpower, and the system is structured from a top-down perspective, where we are opening up spaces, and accepting as many residents for the projected amount of senior positions, rather than catering for how many junior doctors are really needed to be on the ground for the day-to-day hospital needs.”

“I want people to acknowledge the dangers of getting doctors to do 30-hour calls and above, multiple times per week – they are harmful to both patients and doctors.”

A sustainable world-class healthcare system needs to address these issues, and support its junior doctors to do their job well, and to the best of their abilities.

As one doctor concludes at the end of a nearly two-hour call: “The overarching thing is that if we take the prestige of the title of ‘doctor’ out of this conversation, just think about any other career that makes the same life-or-death decisions that we make, and works the number of hours, and gets the amount of pay that we get. If it were anybody else, or any other profession, nobody would want to do it.

He continues, “It would be unfathomable for anybody to say that this should be how it works. Because if we are making such big decisions for 30 hours non-stop without sleep, if this was not a doctoring job, or let’s say it was SCDF, or some other urgency kind of health profession, nobody would want someone to respond to them [after] 30 hours without sleep. That’s where this whole conundrum comes from.”

*According to a sample National University of Singapore Medicine Agreement for AY2021, liquidated damages are “computed based on the subsidy granted by the Government and is disbursed by the Government compounded by an interest of 10 per cent, per annum”. The tuition grant is S$132,500 per annum for AY2021/2022. Based on this number and five years of undergraduate study, the bond is S$889, 817.

NOTE: TheHomeGroundAsia wrote to the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Health Holdings before the publication of the story, for comment about the survey results. MOH directed TheHomeGround Asia to a Parliamentary reply about workplace harassment, and guidelines for the well-being of doctors that it shared in a forum letter. MOHH replied to find out more about the survey and TheHomeGround Asia, but stopped responding after we replied to their questions.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.

Reasons enough to quit

Reasons enough to quit New Innovations: A system to regulate hours

New Innovations: A system to regulate hours