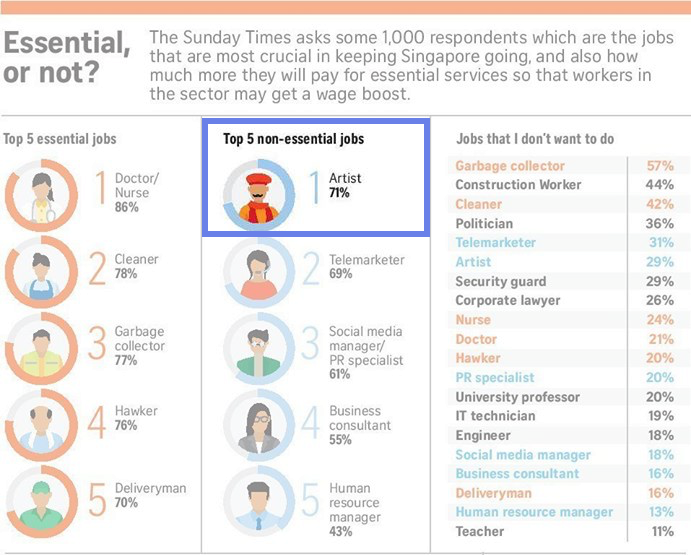

It was in June 2020 that The Sunday Times published a bold survey listing artists as the single most non-essential job in “keeping Singapore going” amid the Covid-19 pandemic crisis.

The Internet community took to social media to denounce the framing of the survey. It also expressed concerns over how the findings could degrade several occupations and deter people from joining them.

The controversy that flared within the arts industry was palpable, to say the least. It has even attracted its own dissenters and supporters. Artists such as local poet Madhu Raghavendra retaliated with the viral poem “Artist”, which spotlighted how the arts are non-essential, until it is not.

While the saga may have died down somewhat, the effects the pandemic had on the entertainment industry have not. There remains little end in sight for the live music scene which has become a faint shadow of what it once was.

Key food and beverage (F&B) locales where people can enjoy live entertainment have not survived the pressures of the pandemic measures, including all seven of the german-themed Starker bar outlets and Switch by Timbre.

Dr Jeremy Lim, an associate professor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore (NUS), told CNN last month that the lifting of restrictions is “important to resuscitate a devastated food and beverage sector.”

The closest the Singaporean government has come to reinstating live music was on 8 November 2021. F&B establishments could now play “soft recorded music”. While unmasking and singing at weddings and events were allowed from Nov 2021, live music at F&B establishments remains banned.

These restrictions were based on the rationale that louder or heavier “background noise” encourages people to speak louder, increasing the risk of Covid-19 infections, CNN reported.

What local musicians are lamenting

“Music was the first to go, and now, the last to come back. As a matter of fact, everything is returning except the arts scene,” says Mr Lai Jee Yon, 33, a prominent guitarist in Singapore’s nightlife entertainment scene.

“This is the time when we really have a chance to grow the local music scene as people no longer have the same options of going out of country for live music and concerts. Everyone is more focused and looking for things to do in Singapore,” says Mr Daniel Sid, 26, one of the country’s up-and-coming singer-songwriters.

By clamping down so hard and restricting all these avenues of performances, this will not be possible, he adds.

At present, sports and fitness activities have resumed. Singaporeans may participate in indoor mask-on, outdoor mask-on and mask-off sports in groups of five, regardless of vaccination status. Up to 30 people are allowed for indoor mask-off high-intensity activity in gyms and fitness studios.

Mr Daniel believes this sends the message that the arts in Singapore is less important — or in other words, non-essential. “With much less ventilation in a confined space where everyone is breathing excessively because of exercise, how much more likely are you to contract Covid-19 from one extra live singer at a bar?” he asks.

“Many performers would be agreeable to safety protocols if it means live music can be resumed,” adds Mr Daniel. These could include putting up an invisible sheet between singers and diners, or mandating performers to take an Antigen Rapid Test (ART) before they go on stage. “There are ways to work around it. It’s just whether the government is willing to ease restrictions and make that happen,” he says.

Countries like Korea, Malaysia, and ironically Wuhan, China have resumed large-scale music festivals as the pandemic becomes normalised.

Where have our artists gone?

Before the pandemic, which seemed a lifetime ago, Mr Daniel would be playing in a different country every month. Back in Singapore, he would be performing up to 13 live gigs a week at bars like Going Om and Timbre.

Being one of the more premium acts, live gigs constituted a significant portion of his income. “To go from seven nights a week to zero is, of course, a very big adjustment,” he says. Thankfully, for him, music has always been his supplementary income source.

Since Covid-19, he has turned towards music production and being a TV host. But if given the chance to perform nightly again, he would go back in a heartbeat.

“It’s not exactly a ‘blessing in disguise’ that I’m picking up other skills. Right now, it has really just been about making the best out of a bad situation,” he says.

Others have not been so lucky. Mr Lai, had been a full-time live performer since he completed his National Service more than a decade ago. Three months into the Circuit Breaker, he knew there was no chance of live entertainment returning for at least the next year.

“With the extra component of live streaming these days, coupled with smaller budgets, things are moving very slowly [for me]. I’m just hanging around, surviving day to day, seeing if there are shows or wedding gig opportunities to hop on,” he says.

While Mr Lai still plays for the occasional wedding, performing over a Zoom screen barely compares to the full experience, for both the audience and himself, he says.

“It lacks a lot of elements. I don’t get to see their smiles and sh*t, I just see one big camera. The guests are all just seated there, they can’t mingle, dance, or move,” he says.

“I’m not the kind of musician who just gets the job done and gets off stage. I like to entertain and connect with my audience. But for livelihood and semi-live music, I’ll keep doing what I do,” he adds.

To pivot or not to pivot?

S-pop veteran George Leong says musicians here are “depressed and feeling displaced”. He even organised a town hall and focus group discussions with the NTUC Union to represent voices in the music industry, which was “in tatters”.

“The main keyword that came up was ‘sustainability’. At that point, we were wondering whether it was sustainable to continue being a musician, and if so, what can we do about it?” he says.

Mr Leong started a fundraising campaign under the name “Singpop Music Limited” to help tide musicians through these tough times, and is working to launch long-term programmes that will support budding young artists.

“The truth is that many pop musicians are self-employed and half take on a second or third job to supplement their income,” he writes on his page.

“Covid-19 has cancelled not only gigs, but has revealed unfair contractual practices. Nonetheless, […] most musicians are committed to music as a career. Because of this, a musician’s work is dignified, despite less-than-dignified working conditions,” he says.

In light of this, Mr Leong believes adapting is essential for local artists to remain…well, essential.

“I think that for survival, we should always keep an open mind. During the SARS pandemic, I became a club DJ because music production was badly affected,” he says. “With our collective industry being rather small, I think we may need to increase our breadth and pick up any work that comes along to help us get by another day to be still doing what we are passionate about.”

Mr Leong, who helped produce one of the nation’s first virtual performances during the pandemic — a rendition of “Home” by Dick Lee featuring 900 participants — finds that maybe it’s time for musicians to engage audiences over digital platforms.

But Mr Daniel depicts the harsh reality for many other struggling musicians. “After depleting some of their savings during the first couple months of Covid-19, many have no choice but to find another job,” he says. “Imagine putting years and years into pursuing your craft, and then suddenly being abandoned in a place where you have to start from zero and learn new skills all over again.”

By stark contrast, Mr Chiya Amos, an award-winning Russia-based Singaporean conductor, worked as a FoodPanda delivery rider when his tours around the world came to a complete halt.

While there were opportunities for him to stay in the music industry — teaching or accepting ad-hoc performance invitations — he chose instead to work for FoodPanda “to not cheapen [his] craft”.

“At least with FoodPanda, I’d get paid fairly by the number of hours that I put in. As musicians, we want to be rewarded for our efforts fairly too. Especially since it’s a passion for many of us, it affects our mental health when we are being regarded as third rate in our craft,” he says.

Intangibly essential

Can we still call the arts essential? Mr Amos wouldn’t jump to label artists as “essential” amid the ongoing pandemic.

“I give my full respect to the healthcare professionals and other frontline workers. But I would say it would be nice if people understand that without artists, the circle wouldn’t be complete,” he says.

“As artists, we have the ability to provide spiritual sustenance for the mind and soul; and that’s what differentiates humanity from other animals and ensures a sort of harmony in the world. Unfortunately, during this pandemic, we are slowly losing that humanity,” he adds.

Agreeing, Mr Daniel believes that music has the power to alleviate the mental stresses of the Covid-19 restrictions. “If you look around, there is so much more conflict. Everyone has this built-up tension and frustration that they don’t know how to relieve,” he says.

Regardless, Mr Amos believes that the problem is not with the media or government labelling the arts as non-essential. “It’s because of the shock and alienation many industries are facing that we start to play this game, comparing who is more essential,” he says.

Rather, there is a general perception that culture is entertainment — and therefore, easily and dangerously considered non-essential. “Unlike entertainment, culture is the preservation of inter-relationships between people, and that’s very important to preserve,” says Mr Amos.

Mr Leong adds that furthermore, music can add as a time capsule. “The songs artists are writing now are actually a snapshot of what our lives are like right now. If we don’t capture them, future generations would not know what we’re going through at this current point in time.”

“When performing is on hold, our dreams are also on hold,” adds Mr Lai.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.