Media and popular culture are often highly sexualised, and in this environment, people who do not experience sexual attraction are viewed with suspicion; their experiences misunderstood and disregarded. But what can the asexual community show us about the ways society might conceive relationships and intimacy differently? As asexuals and advocates celebrated the inaugural International Asexuality Day earlier this month (6 April), TheHomeGround Asia speaks with a few individuals in Singapore who identify as asexual to learn more.

‘You just haven’t had good sex yet.’

‘You need to have sex with the right person.’

This is how 35-year-old journalist Teng Yong Ping’s friends responded when he came out as asexual to his friends. It is a sentiment echoed by 24-year-old theatre director Rebecca G, whose friends have said to them, ‘Do you need to see a doctor?’

For many people who identify as asexual, these are typical remarks from people who do not understand what asexuality is – which is to say, a large segment of the population. Yet it is a reality they have been coming to terms with ever since they realised that their sexual identity was different from most of their peers.

Mx G was about four or five when she first encountered the concept of asexuality: “I was reading an encyclopaedia, and I chanced upon this page about yeast budding in a section on asexual and sexual reproduction. I remember thinking to myself that this is how I wanted to be in the future. In my tiny mind, as a child, that made perfect sense.”

Her younger self had identified with the notion of self-sufficiency, which the biological concept of asexual reproduction implied, even though it is quite different from asexuality as a sexual orientation in humans.

Not all asexual people come to the realisation this early – Mr Teng only recognised that he was asexual at 30. Unlike his male friends he did not watch porn and when he admitted as such, one of them suggested, ‘Oh, you’re probably asexual.’

It was not the first time he had encountered the term ‘asexual’, but it was the first time he had considered that the concept might relate to him: “I went home and I started researching about it online. As I started reading about it, a lot of questions came up.”

So, what is asexuality?

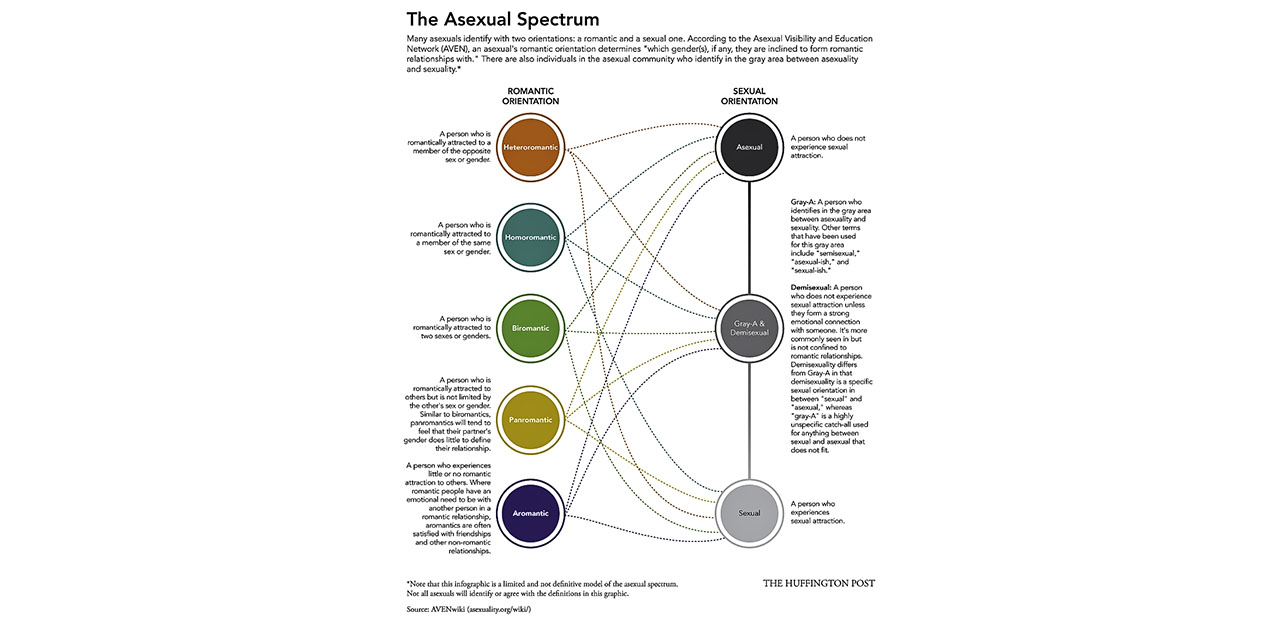

In short, someone who is asexual neither experiences sexual attraction nor, according to the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN), “an intrinsic desire” to have sexual relationships. People who identify on the asexual spectrum are also known as ace, or aces. Notably, being asexual has nothing to do with whether a person has sex, or how much or with whom. By contrast, people who experience sexual attraction and desire are referred to as ‘allosexuals’.

Estimates for the asexual proportion of the population are limited and may vary. But AVEN states that the most widely cited figure is that about one per cent of the population is asexual.

Asexuals generally think of sexual attraction as distinct from romantic attraction, hence their sexual identity is viewed as independent of their romantic orientation. Mr Teng, for example, identifies as asexual but homoromantic, meaning that he experiences romantic attraction to other men, although he is not sexually attracted to people of any gender.

On the other hand, Mx G identifies as both asexual and aromantic, meaning that they experience neither sexual nor romantic attraction.

Others may identify themselves somewhere on the asexual spectrum, or ace umbrella, such as demisexual (finds sex with others undesirable unless a deep emotional bond has been established) or graysexual (seldom experiences sexual attraction).

A journey of self-discovery through the underrepresented web of mainstream media

Living in a society where media and popular culture are highly sexualised has not made it easy for aces to understand their (a)sexuality.

While the allosexual majority can expect to watch their dreams and desires reflected in the lives of fictional characters on the small and big screens, asexuals and aromantics are more likely to be confused about how disengaged they feel towards mainstream entertainment.

“I didn’t experience puberty the same way as my peers – I couldn’t join in in many of the conversations, because I couldn’t talk about the things that they were interested in,” shares Mx G. “All they wanted to talk about were characters that they saw on TV whom they felt were attractive, but I couldn’t relate to that at all.”

They add, “I would go along with the conversations, but I was just parroting what people said so that I could feel my way around and blend in easily.”

In fact, Mx G’s first role model was Sherlock Holmes, the legendary private detective created by British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. They point out that he was one of the rare iconic fictional characters for whom romance was not a significant part of his story.

“Even at a young age, I really identified with how he just had a very good friend but not romantic liaisons – not in the books at least – and I always thought that that was what I wanted,” they explain. “He’s celebrated for what he does and people accept that weirdness about him because he’s so good at what he does.”

These days, asexuality has received slightly more representation on TV, such as characters Todd Chavez in BoJack Horseman, Lord Varys in Game of Thrones, and Florence in Sex Education. The increasing awareness about asexuality has also led to coverage that highlights asexual representation in popular culture on media platforms like Vox and BuzzFeed.

Nonetheless, the lack of a strong, visible asexual community has motivated Mx G to produce art that people like themselves can relate to.

“I want to make work that I want to see, that will speak to people who are like me, or who are interested in knowing more about people who are like me,” says the theatre director, who recently staged a play entitled parthenogenesis, at The Substation. Parthenogenesis explores the themes of asexuality, and is modelled on Mx G’s experiences as an asexual person navigating through life.

University student Alia Alkaff, 24, a co-creator and the solo performer of parthenogenesis, also identifies as asexual. She thinks that those with a platform have a duty to empower others to tell their own stories.

“I know what it’s like to have your story be told by someone else, or be edited and censored just because it’s not in a digestible format for the majority audience,” shares Ms Alia. “So if I have the opportunity to create my own content that speaks to LGBTQIA issues or the issues of the brown community, I would very much like to do that.”

Asexuality and romantic orientation – know your terms

- Asexual – People who do not experience sexual attraction or a desire to have sexual relationships. They also think of sexual attraction as distinct from romantic attraction, and view their sexual identity as independent of their romantic orientation.

- Ace/Aces – People who identify on the asexual spectrum, or ace umbrella.

- Allosexuals – People who experience sexual attraction and desire.

- Demisexual – Finds sex undesirable unless a deep emotional bond has been established.

- Graysexual – Seldom experiences sexual attraction.

- Aromantic – Experiences no romantic attraction.

- Homoromantic – Experiences romantic attraction towards those of the same gender.

- Heteromantic – Experiences romantic attraction towards those of the opposite gender.

- Panromantic – Experiences romantic attraction to people of all gender identities.

Being a minority within a minority

Ms Alia discovered her asexuality in her teens, when unlike her friends she was not sexually attracted to the opposite sex. Speaking to the loneliness of the asexual experience, she says, “I never wished that I wasn’t asexual, but I wished that there were more people like me that I could talk to, who could understand my experience.”

She has since come out to her siblings, who have accepted her ace identity. But she remains hesitant to tell her more traditional-minded parents.

Like other aces that TheHomeGround Asia spoke to, Ms Alia relied on the internet to learn about asexuality, as she felt that she could not turn to her immediate circle of friends and family for information about it.

For aces who are not aromantic, it can also be a challenge to find romantic partners who understand and accept their lack of sexual desire.

“I do yearn for the companionship of a partner,” reveals Mr Teng. “It would be nice to have a partner to cuddle with, to hold hands with, to do all the romantic things that people do… but one big problem for aces is that we often have a much lower libido than our partner.”

This incompatibility can be a dealbreaker for allosexuals, who view sex as an important part of a romantic relationship.

“I guess every ace person needs to negotiate their relationship to touch, intimacy and sex with their partner. There’s no one size fits all,” rationalises Mr Teng.

Square peg in a round hole

Biomedical scientist Chrissie Lim, 32, identifies as heteromantic (romantically attracted to people of the opposite gender) and graysexual. She describes her experience as “one big theme of loneliness”.

Dr Lim passes as straight and feels “out of sync with both allosexuals and the queer community in different ways.” At 25 years old, she suspected that she might be on the asexual spectrum after accepting that she had a low sex drive, despite her best efforts.

“I realised I was never going to experience what my peers and boyfriend described to me about their libidos despite a lot of trying to build a sexual spark,” she says.

“[My then-boyfriend] made the effort to understand the concept of asexuality and tried very hard to be mindful of my consent, but I think it damaged our relationship because he felt ‘unwanted’ when it was obvious I wasn’t expressing my desire for him in a way he recognised – which is to say, sexually.”

When she faced struggles in her romantic relationships and sought support in her friends and family, she was usually met with unhelpful responses that invalidated her experiences. Not being understood has made her feel like she is “struggling” alone in her “pain”, resulting in her feeling unseen or unsafe about this aspect of her life.

“In conversations with allosexuals, I hit a wall whenever I want to have a deep conversation about emotions and companionship,” explains Dr Lim. “Nearly everyone whom I open up to puts a lot of emphasis on sexual needs… and they always assume that romantic and sexual desire come together.”

As for finding solace in the queer community, Dr Lim says that being cis and passing as heteronormative challenges her sense of belonging in any community.

“In the LGBTQ+ discourse, I completely relate to accounts of asexual experience and their struggles, but am also fully aware of my privileges as a cis female with a very femme body, who has only felt attraction to males,” she explains.

“I often feel guilty and unsure if I should consider myself queer since I don’t experience the same challenges as many in the community. Notably, I rarely have to fear for my physical safety or that my partner will not be accepted, since me dating a man would pass as default straight.”

Despite not fitting into the queer community, Dr Lim says that she tries to be a good ally, although she worries about “co-opting [or] usurping the queer space for those facing far more discrimination than I do.”

Her decision not to speak up in those spaces about her problems has invariably led to her feeling “silenced”, though she acknowledges, “through nobody’s fault.”

Finding small pockets of community

According to a 2019 report by the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law in the US, statistics show asexual sexual minority adults report more everyday discrimination and stigma than non-asexual LGB (lesbian, gay, bisexual) adults.

That said, life is not all doom and gloom.

Asexuals can and do find understanding, intimacy and kinship amongst allosexuals and fellow asexuals.

Ms Alia is in a committed relationship with an allosexual man, who has been understanding and respectful of her needs.

“It never occurred to me that I as an ace could be in a relationship with an allosexual and they would be comfortable and want to be with me,” she says.

“One of my biggest fears has always been whether my partner will ever be okay with me being asexual – will I always need to be uncomfortable and be put in this situation where I have to compromise my own comfort in order to do what’s expected of me as a Muslim wife?”

Others like Mr Teng have carved out a safe space for fellow aces to understand their identity. Since 2016, he has been running a Meetup group for asexual people called Aces Going Places. As the group’s description states, it invites “asexuals of all stripes in Singapore to make friends and share [their] experiences so [they] don’t have to feel isolated in an overly sexualised world, where people like [them] lack visibility.”

He explains, “We state specifically that the group is open to non-asexuals or people who are questioning [their identity]… It’s good for us to also educate non-asexual people about us.”

Such an open and welcoming attitude seems to be typical of the aces TheHomeGround Asia met.

As Mx G puts it, “When it comes to the asexual community, there’s always this sense that you’re welcome to identify however you want.”

Hence if a person feels that ‘asexual’ is no longer a label that applies to them, they can feel free to leave.

“That understanding that sexuality is fluid, and everyone’s welcome and valid regardless, makes for very little judgment and gatekeeping,” she says.

Alternative relationships: For a more inclusive and compassionate future?

With asexual individuals feeling uncomfortable, or worse, excluded from society’s default frameworks for understanding relationships, some have found greater fulfilment in alternative modes of intimacy and romantic connections.

Theatre director Henrik, 34, an asexual who identifies as non-binary and panromantic, subscribes to the concept of relationship anarchy, coined by Swedish writer Andie Nordgren. It might sound radical, but what it advocates is for people to decide the kind of relationships they want for themselves, rather than rely on societal norms and pressures.

“I believe that romantic and sexual relationships do not automatically trump platonic or familial relationships,” says Mx Henrik, highlighting one of the key principles of relationship anarchy; that “love is abundant, and every relationship is unique”.

This movement also accepts that relationships can form from different types of attraction, in contrast to how society at large tends to conflate sexual, aesthetic and romantic attractions.

Mx G shares this view: “We can have different kinds of intimacy. The fact that you don’t need a partner to feel complete, and that your friendships can be as valuable and rewarding as romantic relationships, is worth considering.”

Aces may turn to these alternative relationship frameworks because existing ones fail to accommodate their modes of care and intimacy. But allosexuals who thrive in socio-cultural paradigms might also benefit from considering the world through this lens.

By centreing relationships on the people involved and encouraging dialogue, individuals might reflect on what kind of connections they want to have in order to lead fulfilling lives. Thus, preventing mismatched expectations in relationships, for asexuals or allosexuals.

In many ways, this could be a more respectful and compassionate way to honour the unique place and value of relationships; familial, platonic, romantic, sexual or otherwise.

Now, wouldn’t that be something?

Join the conversations on THG’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.