Many Singaporeans in the 1980s would avoid tattoos like the plague and tattooed individuals would be the anecdotal “bad eggs” — symbols of affiliations with the gangsters and secret societies.

In a survey conducted by YouGov in 2019, it was revealed that nearly two in five (38 per cent) said they have a negative impression of people with tattoos. This is particularly true for those over the age of 55, where over half (53 per cent) have a bad impression of tattooed people. This is compared to a quarter (26 per cent) of those aged 18 to 24.

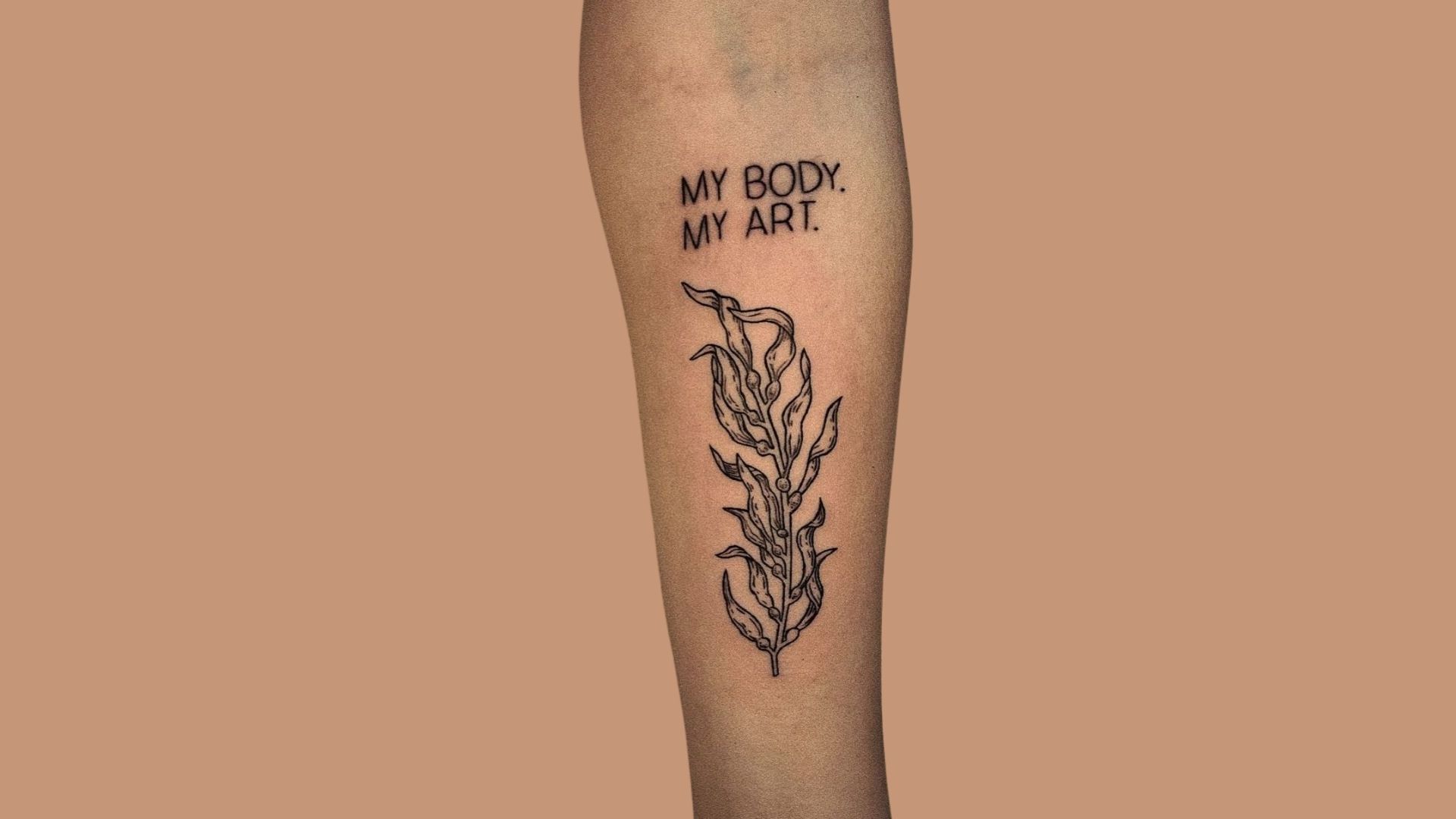

But how about today? Many would argue that we see a reclaiming of tattoos as an art form, self-expression, and control over one’s body. Unsurprisingly, the style of tattoos people would design and go for has also evolved alongside this sentiment.

Full-time tattoo artist of two years Catt Maiyeh (@catt_ass_trophy on Instagram) says In the last five years there are fewer rules and “anything can be a tattoo”.

“There weren’t many tattoo artists venturing out of what would qualify as a ‘traditional tattoo’, but now there are way more artists doing many different styles, and even trying out new approaches to traditional tattoo designs,” she says.

People are starting to realise that it is “really not that deep — sometimes it’s just fun,” she adds.

But has this newfound liberalism penetrated the workplace? How do tattooed individuals navigate workplaces that have yet to catch up with this inconspicuous rebranding of tattoos, especially among the younger generation?

Some Singaporean employers still less likely to hire people with tattoos

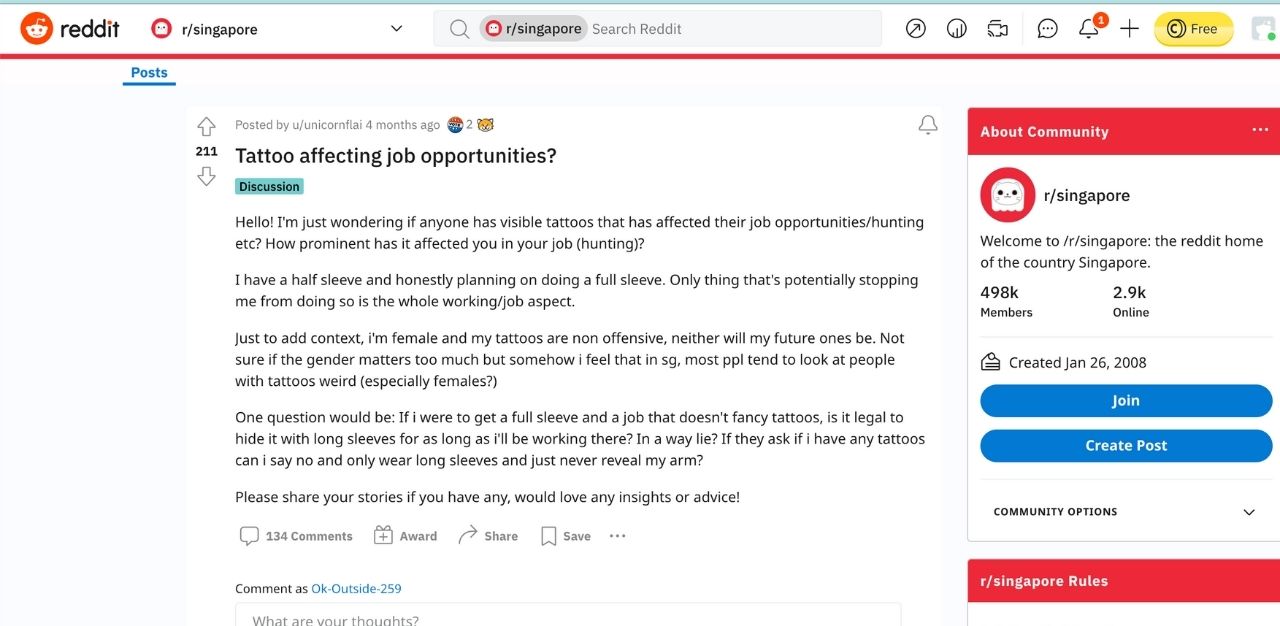

A recent post on Reddit’s Singapore community titled ‘Tattoo affecting job opportunities?’ had been upvoted over 216 over the past four months — an indicator that there is still much ambiguity over whether tattoos have truly found acceptance in the workplaces in Singapore today.

One popular comment discerned between industries and jobs, with the commenter citing that her colleague at a conservative corporate company in the sales department was “gone within one month of joining [the company]”, and that could be partially attributed to his tattoos.

Others suggested wearing long-sleeved shirts to cover full tattoo sleeves up at work at all times, as well as during job interviews.

This is what Dr Alex Yeo did when he first went for his interview with the Ministry of Health (MOH). “I was worried, which is why I wore a suit. I did have long hair at the time as well, and they could see that. I didn’t really feel the need to declare that I had tattoos at the time either,” he says.

Tattoo: An art form more than skin deep

Now completing his residency at public hospitals, Dr Yeo admits that he does “kind of stick out like a sore thumb”, being a tall, long-haired, tattooed doctor.

He doesn’t like to cover his tattoos at work for three main reasons: He doesn’t think it’s necessary; it’s very warm, especially being in Singapore; and with Covid -19 now, wearing long sleeves may increase the risk of transmission when interacting with patients.

“It doesn’t really hold any particular strong meaning or anything, I just really like the art form and it’s something I wanted to do for myself,” says the British-educated doctor, who got his first tattoo during his second year of medical school.

When asked whether it ever crossed his mind that his tattoos would interfere with his particular line of work, he says he definitely took a risk in believing that it would not have mattered. “Tattoos to me are just another form of self-expression, and I feel that if they’re not offensive and are not harming anyone, I don’t see why they should be a problem,” he adds.

Fortunately, his experience at Alexandra Hospital (AH)— the first public hospital he was attached to — did not disappoint. “I got along really well with the seniors there and everyone was very encouraging, and even encouraged me to apply for residency. No one made my tattoos a thing, and I’m really grateful to AH for that,” he says.

“I worked together with Dr Yeo at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. He is a very diligent and responsible doctor. He has a good work attitude, and doesn’t shy away from taking on more responsibilities and work,” says former colleague Dr Liew Mei Fong, a consultant of the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at AH — a clear reflection that external appearance plays little part in the hospital’s success quantifiers or selection process, tattoos included.

This is not to say that he doesn’t still get raised eyebrows at work.

“Obviously, people are curious, but they don’t react badly to them. I’ve had colleagues who would ask me about the background of my tattoos, and some would tell me that they wouldn’t know how to talk to me at first. But I’ve become really close to a lot of my colleagues who have, of course, realised that I’m just like anyone else working at the hospital,” he says.

Patients would periodically tell him, “nice flowers” or “I didn’t know doctors could have tattoos, that’s cool”, while the older patients, surprisingly, don’t really care, Dr Yeo adds.

On occasions, he would be able to sense that his tattoos were making someone slightly uncomfortable — such as when nurses avoid addressing him directly, triangulating simple conversations despite being in the same room.

In such cases, Dr Yeo does not mind going the extra mile to make sure they know that he is completely approachable — such as taking the initiative to interact more with them and asking about their day. “I didn’t get tattoos to make the people around me uncomfortable — and I don’t really have to do it that often anyway,” he says.

Since his time at AH, however, he has moved on to other public health institutions, and realised firsthand that not every hospital shares the same views.

At one restructured hospital, while his supervising senior did keep an open mind about his tattoos, the culture was palpably more conservative.

“Apparently, some of the clinicians and nurses had sort of raised a few eyebrows — or so I’m told. And I was asked if I’d be willing to cover my tattoos,” he says, citing his discomfort with the way the situation was handled.

While he believes that his senior did not have any personal qualms against his tattoos, he found the feedback given to him vague.

“All the colleagues whom I’ve spoken to are alright with it, so from my end, it seems like there is this nebulous group of people who wanted me to cover up my tattoos, and I’m under the impression that this is by far the minority,” he says. “We spoke a lot about it, but I still didn’t know what the real concern actually was.”

He ended up complying to avoid further conflict.

While he understands that they have a certain image to uphold and people to answer to, Dr Yeo’s perception is that these perceived concerns come more from the organisation’s rather outdated expectations on how patients might react.

“The reason why tattoos have a stigma in the first place is that they used to be associated with people of shady backgrounds in the past, but that is obviously not the case now. Sure, people in illegal organisations still might have an attachment to tattoos, but so do a lot of other groups of individuals now,” he says.

“The conversation around my tattoos has been a lot more extensive than I would have liked it to be. For me, I just want to come to work, tend to my patients, hopefully, do a good job, and then go home,” he adds.

Further, if tattoos were truly a concern for the exceptional patient, Dr Yeo would have liked to see the organisation that he works for step up and in the testimony of his capabilities, instead of his appearance — and be part of the narrative change for individuals like himself, who get tattoos purely for the art of it.

“Maybe it’s a bit of wishful thinking on my part, and maybe we’re not that progressive yet, but hopefully we’ll be able to see that happen someday,” he says.

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.