(CONTENT WARNING: The article contains descriptions of self-harm and suicide.)

Note: Advice given here does not replace professional consultation. If you, or someone you know is struggling, do consider seeking professional help. Self-harm here is also discussed in the context of non-suicidal self-harm, and should not be confused with self-harm with suicidal ideation. Always seek professional emergency assistance if a person’s life seems in immediate danger.

I was 11 the first time I placed cool metal on my skin.

It started out as sheer curiosity. I had seen a classmate cutting herself, and thought it would be a ‘cool’ thing to try out. The wounds were superficial at first, barely breaking skin, easily passing off as an accidental scratch or a nick from a pair of scissors.

This was my induction into the world of self-harm. In the beginning, it was innocent, not quite harmless, but not yet a huge cause for concern.

Heng Si Yun’s journey started out in a similar fashion. At 12, a friend had shown her how to cut her arms, claiming that it “made her feel better to let out her emotions this way.”

For us, and many like us, we were initiated into the world of self-harm young. According to a counselling psychologist at Annabelle Psychology, who goes by just one name, Diana, the typical ages are from upper primary to lower secondary (between 10 and 15 years old).

“If they [children and youths] were to see people around their age who engage in self-harm, they will be more likely to try even if they’re not experiencing any significant form of pain. It’s more of curiosity,” Ms Diana explains. “And then after that, they learn that next time when they have problems or difficulties, this is one way they can cope.”

She adds: “There could also be peer pressure. If a lot of peers have self-harmed, it [becomes] accepted or endorsed as a coping mechanism.”

Over time, these behaviours borne of curiosity can easily transform into something more insidious and dangerous, if left unchecked and unaddressed. As Ms Heng and I entered adolescence, with all the emotional turmoil that came with it, we soon associated what we were exposed to in our childhood years as a viable means of coping.

When hurting ourselves was the only thing that made sense

The point where the act transformed from mere curiosity to sinister coping mechanism is a blur, lost to the passage of time. But the low points, I recall with absolute clarity; for in the years that followed, the blunt pair of scissors became penknives, and shallow scratches became cuts that left scars.

The sharp edge of a blade slicing through skin became the only refuge that I knew as I struggled with my mental health, and it continued to be that way in the years after. Self-harm had become the only way I could manage the tidal waves of emotions, and not drown from their sheer force.

These struggles, I will later learn, is something I am not alone in dealing with, and a common reason why people engage in self-harm behaviours.

Ms Diana says: “One of the common reasons for [self-harm] is that the physical pain is in itself a form of distraction from the psychological pain that they feel. For some, the psychological pain they experience can be so intense and overwhelming that they feel emotionally numb. Self-harm then functions as a way to help them feel alive.”

For Ms Heng, self-harm featured more prominently in her life during early adolescence. In the face of a teenage heartbreak and traumatic memories of being sexually assaulted as a child, she turned to the coping mechanism that picked up in her pre-teens, and began hurting herself again to cope.

“At that time, it felt like I was hurting so much emotionally and was feeling like I was losing control,” she recounts. “Self-harming was one way to take back control by being able to choose what kind of pain I felt. It was also a way to express all the pain that I was feeling emotionally, in a physical way instead.”

Ms Diana explains this phenomenon: “In situations where [individuals] feel very helpless, self-harm can sometimes help them feel like they’re in control of the situation. They can rely on this act to exert their control, exerting a sense of mastery that ‘I’m still here, and I’m doing something’.”

In addition, self-harm can be a form of self-punishment. “[If] a person feels that he or she is not deserving, or a very strong sense of unworthiness, sometimes, self-harm can help them feel like they are aligned with what they view of themselves,” she explains.

My own experiences with self-harm inform me that it is rarely just one reason or incident that leads to an individual hurting themselves. Oftentimes, it is a culmination of factors. The reasons Ms Diana brought up all rang true to me, with some being more dominant than others.

During my teenage years, self-harm was the only way I knew how to make sense of my emotions, a conduit through which I could process the intangible in a physical form. At my lowest, I carved words into my skin to remind myself of the physical pain I believed I deserved.

And while the reasons why people self-harm are as multifaceted as individuals themselves, there is one thing that it was not – attention-seeking.

What self-harm is not

When I first started hurting myself, I would cut myself on my wrist and arms, because that was the norm that I had been exposed to. Eventually, I learned that hurting myself in these areas drew too much attention.

Hurting myself was not something I wanted to flaunt. Far from it, in fact. I wanted it to be as hidden as possible. I did not want to have to answer questions on the ‘why’s, or hear that it was wrong, or handle loaded glances of pity and disapproval. Over time, I learned to hurt myself in places that were hidden from plain sight, and to cover up my scars with long sleeves, bracelets, scrunchies, and anything that would not look out of place.

Ms Heng pleads: “I wish people would understand that [self-harm] is not necessarily for attention.”

Writing self-harm behaviour off as merely a cry for attention and trivial can be dangerous. Ms Diana stresses: “This may not only maintain, but also worsen the pain that this person has.”

Another common misconception people have is that self-harm equates to suicidal ideation, which is not always true, according to Ms Diana.

Nevertheless, the risks of self-harm are still worrisome. Ms Diana highlights that while it can serve as a temporary coping mechanism, it is unsustainable in the long run, and may lead to a downward spiral.

“Self-harm provides a temporary relief, but it doesn’t address the issues behind the psychological pain,” she explains. “There is a likelihood that the more you engage in it, there may be an increase in the severity of the behaviour, and this brings about more risk and complications.”

She warns that if engaged over a period of time, self-harm behaviour can become addictive, because it is predictable: “[Sentiments like] ‘I know that when I experience pain and I cut [myself], I feel alive. I can count on this.’ So each time an individual does it, they know that they will feel this way… it becomes an addiction that may be more difficult to break away from.”

It is also important to recognise the different forms of self-harm that may be less visible than self-cutting, says Ms Heng. This can include burning, scratching, pulling one’s hair, punching walls, or hitting one’s head on the wall.

With some forms of self-harm being invisible to the naked eye, and the propensity to hide self-harm behaviour, Ms Heng underscores that self-harm is never a joking matter: “[Jokes] can potentially trigger someone that you don’t know is already struggling with it.”

Paying attention, offering understanding, and being present

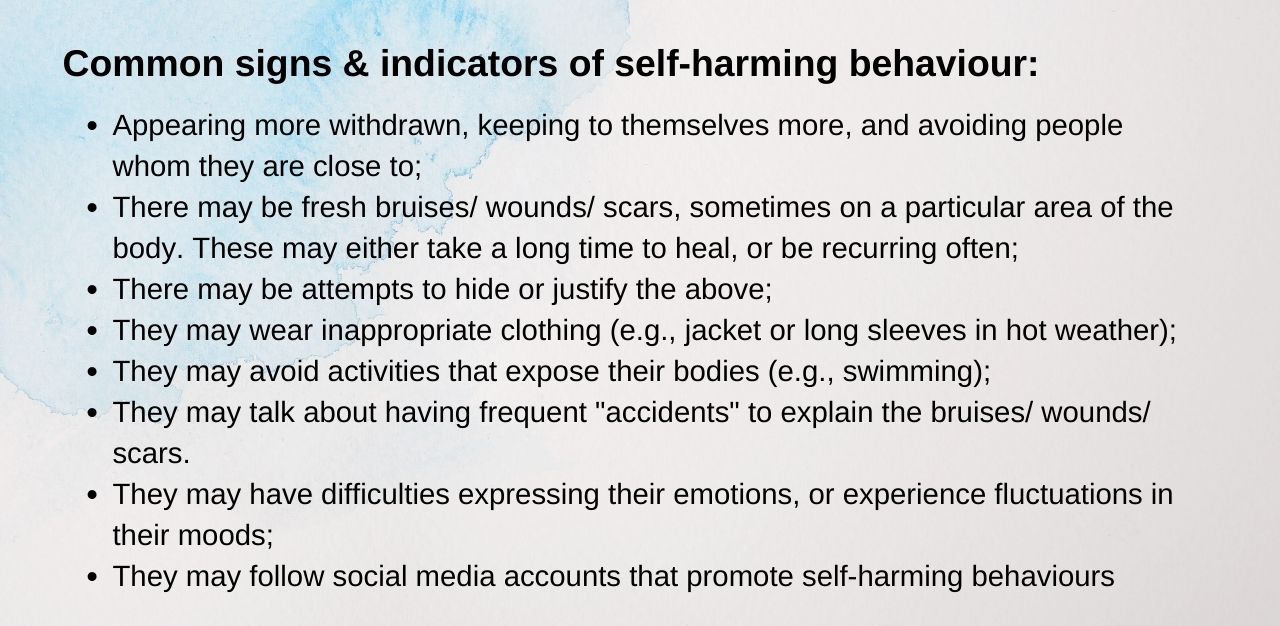

While an individual is often inclined to hide their self-harming behaviour, the community around them can still pay attention to warning signs, and offer support. Ms Diana provides some common indicators that an individual may be hurting themselves.

If uncertain, she advises outsiders to share their observations without judgement: “You can say, ‘Oh, I noticed you’ve been quieter recently, or I noticed that you’ve been wearing long sleeves, even though it’s been really warm, and I’m concerned that something may be going on.’”

She also asks that people resist the urge to offer help and to suggest solutions: “If this person is not prepared [to seek help], it may make them withdraw within himself or herself more. You can listen first, and validate what they are going through.”

Another thing that a person can do, she says, is to help the friend, acquaintance or loved one to identify emotions, like feeling helpless: “Ask for permission to suggest [solutions]… Do it in a very gentle way, rather than in a critical manner that pushes them away.”

Attempting to guilt-trip an individual into stopping such behaviour is not helpful either, Ms Heng points out: “I understood their concern, but at that point of time, it just made me feel worse and added to the emotional pain I was struggling with.”

“Instead, what helped was when friends were understanding and supportive when I relapsed,” she says. “I also had friends that got on long calls to distract me [when the urges arose].”

When it comes to professional help, it is best dealt with sensitively and carefully.

In the years that I struggled with self-harm, I received one too many offers of intervention from well-meaning loved ones, who thought they were helping but only made things more difficult. At a time when I was not yet ready to recover or to seek help, having friends call out my behaviour, or threaten to report me to professionals, only drove me further into my shell, and made me more adept at hiding the signs.

In cases where an individual is unprepared or unready to seek advice, counselling or an intervention, Ms Diana suggests being available and jointly exploring ways for them to “soothe themselves in a more healthy manner”, as opposed to relying on self-harm. She also recommends to check in often with the person who is self-harming to maintain open communication.

“Being non-judgemental is very important,” she emphasises. “You want to let the person know that you want to understand, you want to support, and you’re doing it in a very open and accepting manner. Don’t force anything on them.”

In short, just be present, she says: “Be around to tell this person that it’s okay, that I’m here for you. And when you’re ready, let’s go [seek help] together.”

While it is wise to seek professional help at an early stage, so that issues can be addressed as soon as possible, Ms Diana says that it is still best to seek permission from the individual before approaching mental health professionals, as the “success of mental health treatment is heavily influenced by personal motivation, commitment, and involvement.”

Ms Diana suggests non-confrontational ways to encourage an individual to seek help, like saying ‘I notice there are more scars, or the scars seem a bit deeper than before, and I’m really concerned. Is it okay if I offer some solutions, or what about I go to a [therapy] session with you?’

But, if the self-harm behaviour escalates to the point of being life-threatening, Ms Diana clarifies that it is essential to encourage them to seek medical assistance to tend to their wounds, and to accompany them if possible. If there is a need for professional intervention in the mental health space, she insists that individuals speak to the person concerned before engaging any.

The personal journey to recovery

Wanting to discover better coping mechanisms and to understand herself better, Ms Heng had eventually sought professional help on her own. But this came years after she had first started self-harming.

“I didn’t try to get better intentionally,” she shares. “At that point in time [when I was self-harming], it felt like the end of the world. But as cliché as it is, it really does get better. I slowly healed and stopped feeling the need to turn to self-harm.”

My story reads similarly; while I had never sought professional help, I eventually developed better ways of coping over the years – writing, reading and taking naps are some of my go-tos.

For individuals still struggling with self-harm, Ms Diana offers this counsel: “I strongly believe in mindfulness and connecting in the present moment,” she says, which would give the person time to examine the intention behind their actions. Oftentimes, adds Ms Diana, the behaviour becomes an “autopilot action”.

Being mindful enables a person to recognise and identify potential triggers that may bring about the urge to self-harm. And these triggers can be many different things, she explains – a smell, a word, an object, or certain visual cues.

Once you have identified your triggers, Ms Diana encourages finding alternatives to substitute self-harming behaviour. For instance, you can talk to someone whenever you find yourself triggered, without necessarily addressing your self-harming behaviours.

“This person can be your go-to person when you notice the urge to self harm,” she explains. “It becomes a kind of substitute behaviour; when you have the urge, you can go to this person, talk to them, and spend time with them until the urge fades.”

The recovery process is by no means a smooth-sailing journey. In the earlier years, every instance of relapse had me ruminating on my own failures, sinking me into a vicious cycle of guilt, self-harm, rinse and repeat.

Ultimately, what helped was recognising that recovery is not a linear process, and that one slip-up does not erase progress. It is a journey I am still on today, 13 years down the road. But being able to sit down and write this piece at all reminds me of just how far I have come, that penning these words no longer triggers me.

And if you are still in the middle of that seemingly unending journey, these are the words that I clung on to, for as cliché as it is: This too shall pass, and it does get better.

Resources and helplines if you need support

If you are, or someone you know is, struggling with self-harm, or just need/s someone to talk to, resources are available:

- Fei Yue’s Online Counselling Service

- CHAT webCHAT Service

- Institute of Mental Health’s Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222

- Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

- Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444

- Silver Ribbon Singapore : 6385 3714

- Care Corner Counselling: 1800 353 5800 (Mandarin)

- TOUCHline: 1800 377 2252

- National Care Hotline: 1800-202-6868

Join the conversations on TheHomeGround Asia’s Facebook and Instagram, and get the latest updates via Telegram.